Social and Affordable Housing: Why Wood Structures Build it Better

06/04/2021 03:20 PM

Author: Paolo Lavisci, Program Development Manager, WoodSolutions MAP

In light of recent funding announcements, Paolo Lavisci of the Mid-rise Advisory Program considers Social and Affordable Housing in Australia and identifies the benefits offered through building with wood.

Social Housing is defined as “affordable housing provided by the government and community sectors to assist people who are unable to afford or access suitable accommodation in the private rental market”. As such, it includes both public housing (fully owned and managed by state and territory governments) and community housing (either owned and/or managed by not-for-profit community sector organisations). Affordable Housing is therefore a larger market segment, which also comprises private development initiatives that address specific targets through a tailored value proposition. Let’s see the differences, the opportunities, and the (wood) solutions for this growing asset class.

Social Housing

In 2017-18, over 1 million low-income Australian households were in “financial housing stress”, spending more than 30% of their income on housing and facing difficulties meeting basic living costs. On 30 June 2019 over 148,500 Australian households were on a waiting list for public housing, down from 154,600 in 2014, with waiting times ranging from 3 months to over 5 years [1]. From the same source, it is interesting to note how the pressure was already increasing before COVID-19: in 2017–18, 11.5% of households spent 30% to 50% of gross income on housing costs, with another 5.5% spending 50% or more, while these proportions were 9.2% and 4.6% respectively in 1994–95. The pandemic compounded these trends, as almost one million fewer people (than previously expected) are projected to be living in Australia by 2025, the largest negative shock to population growth since early last century. Hence the significant role that the last Federal budget attributed to Social Housing as a major stimulus tool for our economy, while also most States have announced additional measures supporting social housing construction. More on this later.

In most cases, tenants of Social Housing are eligible for a rent subsidy, which results in them paying rent based on 25% of their gross household income, plus 100% of the Commonwealth Rent Assistance. In comparison to similar countries, Australia has quite a small percentage of Social Housing properties available which is continuing to decline from 5.1% of all housing stock in 2001 to 4.2% in 2016 [2]. As a reference, the UK have about 20% of all housing stock devoted to social housing, and Canada about 6% with a significant funding effort started in 2017 ($40B over 10 years) to build 100,000 new affordable units, repair 300,000 affordable units and cut homelessness by 50%.

Affordable Housing

A broader definition of Affordable Housing is “a product available to low-to-moderate income earners, who are working but may find it difficult to afford housing in the private rental market”. As such, it refers to both prospective buyers and tenants, with an aim to relieve short-term rental stress and support households that have the potential for income growth or homeownership in the medium term. Filling the gap between Social Housing and the private housing market, it typically targets the needs of “frontline workers” who have a place-based job, and whose salary potential is capped at a low to moderate level. That includes nurses, teachers, paramedics, firefighters, and childcare workers, but also many administrative staff, bus and delivery drivers, hospitality and retail workers, social workers, care workers and others. These people require and indeed deserve, a comfortable living standard, allowing them to thrive and contribute to making Australia a better place. Rental Affordable Housing is not offered as a long-term housing solution but is designed to meet short or medium-term needs. The eligibility of tenants is assessed on an annual basis, and their permanence in the system is only a mean, not the end goal. But unfortunately, the State of the Nation's Housing report [3] just released had to acknowledge that “longer-term trends of declining affordability, particularly for low-income households in the private rental market and prospective first home buyers are likely to persist, particularly if supply is not responsive to demand when it recovers”. And this accounts for the difficulty to start Rent-To-Buy and Co-Housing initiatives, which are becoming a rather popular model among the Millennials, in both North America and Europe.

Anyway, Affordable Housing needs are here to stay and will be implemented in a variety of forms. As an example, the significant growth in Build-To-Rent initiatives cannot be explained only by the recent fiscal support to the sector, but rather by the developers’ quick understanding of the changing demand and sectorial depth [4]:

- Mirvac has led the charge, launching its $1B Build-to-Rent Club and securing the Clean Energy Finance Corporation as a 30 per cent cornerstone investor.

- More than 30 major build-to-rent projects, from all the major developers and with an average size of 365 apartments totalling 11,700 units have been confirmed across Australia, with an additional pipeline estimated at more than 10,000 units currently in due diligence.

Strategies and funding opportunities

In the last Federal budget expenses for Housing are estimated to increase by 34.1% in real terms from 2019–20 ($4B) to 2020–21 ($5.6B), as follows:

- The Housing section, through the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, the provision of housing for the public (HomeBuilder) and people with special needs, housing support through the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation and Defence Housing Australia expenses.

- The Urban and regional development, with City and Regional Deals, services to territories and regional development programs, including Community Development Grants and the Building Better Regions Fund.

State Governments have also committed quite significant funds:

- The NSW Government announced a new social housing package with $812m to build more than 1,200 new dwellings and upgrade over 8,000 more. NSW’s existing social housing strategy will continue and is committed to delivering up to 27,000 new and replacement social and affordable dwellings over 10 years, although it looks like the number of houses delivered will fall short of this. Moreover, the Government has recently engaged with underworked commercial builders for social housing. Further information on [5].

- The VIC Government announced a social housing scheme of $5.3b to construct more than 12,000 new homes over the next 4 years. A further 2,900 homes will be delivered to help low-to-moderate income earners live closer to where they work and provide options for private rental. All new homes will meet 7-star energy efficiency standards. A new agency, Homes Victoria, has been established to work across government, industry, and the social housing sector to both deliver this new housing and manage existing public housing, with a fast-tracking of selected projects [6].

- The QLD budget offers a $100m “Work for Tradies” scheme [7], which draws on existing government landholdings, accelerates local construction, and identifies new opportunities for house and land packages to support the delivery of social housing in high growth areas. This scheme is purported to result in 215 new social homes over the next 12 months. This complements the existing 2017 Queensland Housing Strategy, which targets the delivery of 4,522 social homes and 1,034 affordable homes by 2027. The Government has also recently engaged with Frasers Property and Mirvac to deliver two Build to Rent projects, each of which will offer a number of homes at a discounted market rate to eligible tenants like health and emergency service workers [8].

- The SA Government announced a $21.4m stimulus package to build 100 new homes, including 71 to be sold as affordable. These homes are set to be built by early to mid-2021. This complements the $550m ‘Our Housing Future 2020-2030’ strategy launched in 2019, which includes $400m to building 1,000 new affordable homes by 2025, with incentives provided for the development of a further 5,000 affordable dwellings. See [9] for further information.

- The ACT Government announced the investment of $61m into public housing, resulting in the construction of at least 260 homes, and the upgrade of 1,000 existing properties. While most of this funding is allocated to maintenance and upgrades of existing properties, $32m of it is allocated in the form of land, and the 12-month extension of the Territory’s “Growing and Renewing Public Housing Program” which already sought to deliver 1,200 new homes by 2024. More information at [10].

- The WA Government announced a $319m social housing scheme intended for the construction of 250 new homes, the refurbishment of 1,500 homes, and a regional maintenance program for 3,800 homes, in addition to the existing “WA Housing Strategy 2020-2030” [11] which intends to deliver 2,600 new social homes by 2030. See also [12] for projects currently planned or under construction.

Why wood structures?

A hallmark of these big-spending announcements is a concerted, progressive move away from public housing, which is owned and managed by the governments, to community housing managed by independent providers and other forms of affordable housing, which can be owned by private businesses. Public and private initiatives, with the latter being strongly encouraged, should have a focus on “maximizing value”, relying on data and evidence to deliver the best outcomes and justify the support received. All the funding schemes, in different forms, outline well-worded sustainability goals. Core principles are meant to “put people at the centre” of the brief, so that buildings will be designed and delivered in a way that is responsive to a variety of needs, including from those who face challenges in addition to affordability, such as disability, family violence or mental illness. Housing should be built for demonstrable sustainability, including being climate-adapted, water and energy-efficient and incorporating best practice design to ensure they are “future-proof”.

Therefore, designing and building social housing with well-optimised wood frame construction systems offers many benefits, as outlined in WoodSolutions’ Cost Engineering guide [14], including:

- Faster construction programs, typically reaching completion up to 30% faster than alternatives.

- Cost savings of up to 15%, when also indirect costs are considered (e.g. preliminaries, installation of services…)

- Reduced weight of the building resulting in fewer or smaller footings, less excavation, and less consolidation in vertical extension of existing structures.

- Benefits for residents in terms of comfort, running costs and maintenance costs, including improved thermal insulation, high-performance acoustic separation, and flexibility for future remodelling.

- Highly durable and fire-safe systems utilising simple design methods to provide a safe, healthy, comfortable, and robust building structure.

- Safer, quieter, and less disruptive construction sites. Prefabricated timber structures can require up to 80% fewer deliveries than traditional sites, limiting risk exposure for the project and reducing congestion of the local area.

- Sustainability benefits associated with using our only renewable building product. Every piece of sustainably grown structural timber locks carbon away from the atmosphere, reducing atmospheric greenhouse gasses and fighting global warming.

- Supporting a $7.3 billion local industry that utilises locally grown resources, driving jobs and economic growth throughout the supply chain.

- Joining many other significant projects in setting an example for the industry by utilising simple off-site fabrication concepts, the future of Australian construction.

These impacts have already been demonstrated on successful timber-framed social and affordable housing projects. Some notable examples in Australia are listed in our case studies [13], plus of course many others overseas, including a few projects from my previous professional life in Italy.

To realise these benefits, we recommend the following key considerations are made early, ideally in the feasibility or conceptual design stage:

- A timber-first design approach utilising load paths and spans that cater to timber’s strengths.

- Engagement with the supply chain to make the most of the industry’s capabilities.

- Involvement of our Mid-rise Advisory Program team, for free and experienced technical support.

References

[1] https://www.aihw.gov.au [2] https://www.ahuri.edu.au [3] https://www.nhfic.gov.au [4] https://theurbandeveloper.com [5] https://www.communitiesplus.com.au/

[6] https://www.vic.gov.au [7] https://www.epw.qld.gov.au [8] https://www.treasury.qld.gov.au [9] https://www.housing.sa.gov.au [10] https://www.act.gov.au

[11] https://www.communities.wa.gov.au [12] http://www.housing.wa.gov.au [13] https://www.woodsolutions.com.au

8 Untapped Opportunities For Construction Productivity - Where Are The Next Blue Oceans?

23/02/2021 11:00 AM

Author: Adam Jones, Structural Engineer, WoodSolutions MAP

Adam Jones of the Mid-rise Advisory Program looks back through some of the key takeaways from three seasons of the popular 'Timber Talks' podcast.

Since starting the WoodSolutions Timber Talks podcast, I've been lucky to speak with; industry CEOs, company founders, technical experts and project leaders. Recently, I have gone through the archives and put together a 'Best Of Timber Talks' (listen on iTunes or Spotify) around the topics of innovation. Many of the conversations touch on the idea of what are untapped opportunities in construction.

One of my favourite metaphors for this idea of disruption and innovation is provided in The Blue Ocean Strategy, written by Renee Mauborgne and W Chan Kim.

The Problem: Current markets in construction are flooded with competition. More and more companies are competing for smaller and smaller profit margins. This cut-throat battle leaves the waters bloody. This is the Red Ocean.

The Solution: Swim away from the competition. Make the competition irrelevant. Find wide open space. Create a Blue Ocean.

Blue oceans are defined by untapped market space, demand creation and the opportunity for highly profitable growth. Some blue oceans are created by sailing somewhere completely new and different, but more often it simply involves an expansion of your current perceived industry boundaries. Largely, blue oceans are the unchartered territory.

Blue Ocean opportunities is a theme I've been pondering on recently. It goes without saying; that understanding where they are is worth noticing; whether from a career, business development, entrepreneurial and skills-to-learn perspective.

In the following article, I've taken the best highlights from the conversations on the WoodSolutions Timber Talks podcast, looking at the untapped forces that can be utilised to sail into the blue waters.

1. Asking suppliers about parameters early

"If we have a client who comes to us quite early on day one to sit down with the architect, we can ask for some parameters that would best suit our solutions. And we can add a huge amount of more value and better cost, program and waste outcomes. It will be a much better outcome for the project."

- Adam Strong, Director at Project Innovator. Season 1 Episode 1

With the traditional construction paradigm, you don't need to get in touch with suppliers until the 'For Construction' drawings have been created. However, this doesn't fly when it comes to manufactured buildings, particularly in timber construction. The architectural intent must be consistent with the material from the very start.

As the saying goes: If you try and fit a square peg in a round hole, you're going to get frustrated. It doesn't matter how much you hammer away at it. You can yell at it, scream at it... but it won't go through. As Adam Strong says the key is to begin with, the right parameters that make sense from a manufacturing and logistics perspective. If the design suits the product, then it is downhill skiing from there.

Kit-of-parts design philosophy

Designing with an idea of material and DFMA parameters are low hanging fruit for improvements starting today. However, in the medium term, this may lead to a kit of parts strategy. This starts with somewhat commoditized parts from the factory that can be combined in a variety of ways. The Department Of Education in NSW leads the way of driving this philosophy with the standardized grids for the school's stimulus.

Commoditized manufacturing, I know is somewhat controversial in construction. We get worried that we'll end up with horrible dog boxes and remove ingenuity from design. But perhaps we can keep the flexibility as we move to a new way of design and construction.

For example, I ordered a Subway for dinner last night. I had the flexibility to choose between different meat, vegetables, cheeses, salads and dressings. There are hundreds of different versions of a Subway I can walk out with all of the intermediary steps. A kit of parts doesn't need to be boring. From a suppliers perspective, it offers commoditized manufacturing ensuring line of sight from the factory. And for the designers familiar with the different parts to play with, it could maintain the much-needed flexibility.

No doubt, early days it might all look like a pretty mundane block of lego. But given enough time, lego designers today can combine them in a myriad of ways to produce really beautiful and interesting structures.

2. Align incentives for all parties

"Basically architects, engineers, general contractors, subcontractors, and all of those parties are cost-plus. So none of them has any incentive to take cost out. And so they don't. It's not a surprise because if the costs go down, they just make less margin and less dollars. Everybody's actually invested in the system of being inefficient. We're 50 years into this. And every time we start a new project, we start it as though we had never built one before, which is exactly the truth. The other way I talk about it is you look at it at architects they design a building that has never been designed before. It has never been built before and will never be built again, which in the electronics industry, we call that a prototype"

- Michael Marks, Co-founder Katerra, Ex interim CEO of Tesla. Season 2 Episode 1.

For example, engineers are on the hook for safety and get paid for by the hour. Typically, the fundamental role of an engineer is to design a safe building. As firms compete to win jobs, inevitably fees are lowered and material efficiency opportunities are lost; adding costs and unnecessary embodied carbon into the building. In the classic prisoner's dilemma, all parties race to the bottom.

Michael Marks and Katerra have the luxury of billions of dollars of venture capital, with the aim to be vertically integrated to solve this problem. Other routes to aligning incentives could be profit sharing between companies on successful projects or building of trust between project proponents.

3. Eliminate wastage

"For example,e a project has 300 toilets and serves 300 residences, right? The cost of a toilet is probably eight, nine bucks at it's origin. But the way it works on the construction site is before the toilet reaches the job site, it passes through, a distributors hands and then the subcontractor's hands, and then eventually the contractor and then gets onsite. Then the developer marks it up. By the time the consumer gets the toilet in their bathroom, it's probably cost them $120. Well, that value shifts for any product in the built environment is enormous."

- Michael Green, Founder of Michael Green Architects. Season 1 Episode 10.

Michael Green is using the toilet as just one example that is representative of lots of processes when putting a building together. Wastage can, of course, be found in many places if you have a look. As stated in a great book 'World Class Manufacturing' by Richard Schonberger it can come in the forms of defects, overproduction, waiting, non-utilized talent, transportation, inventory, motion and extra-processing. Apply these frameworks to all professions and you might be able to find opportunities around eliminating waste.

For example, Rob De Brincat pointed out in a few seminars in 2019 a whole lot of unnecessary motion with the tender matrix. In the traditional D&C model, 4-5 builders, speak with about 30 trade categories and about 4-5 subcontractors per trade category. If one builder wins, the whole process is (30/500) 6% efficient. All that unnecessary work is flushed down the drain. As Rob suggested, this is somewhat improved with early contractor involvement (ECI).

4. Increase cost certainty

"So we think the whole concept of certainty for the developer. It is a big way to drive down the cost for the building. If a developer knows that they can get this building delivered and built in a certain timeframe, doesn't have site problems and if they know the materials are all available because they're all coming out of a factory, it all becomes very predictable. And if we can price all those materials exactly the way that the factory can order them, we now create this whole environment of certainty. When you create that the owner now has a much better financial picture of what he can deliver."

Karim Khalifa - Director at Sidewalk Labs (an Alphabet company). Season 2 Episode 12.

At the beginning of a project, there are unknown unknowns that are discovered along the way. As Daniel Kahneman pointed out in Thinking Fast And Slow, we should be accounting for a 30% increase in the program for projects that are new. Before a project begins, the planning fallacy holds inherent uncertainty around what the costs might be.

Currently, we design everything once. Whether be engineers, architects, building surveyors and fire engineers. We go through the same process for every new job and deal with the uncertainties around unanticipated complexities along the way. And when the next project comes along we do it all again, embedding the planning fallacy into every project.

Designing this 'environment of certainty' is a big step for all designers, builders and suppliers for project teams. And perhaps it is something that can only be solved with vertical integration between supplier and builder (and developer?). But whoever can confidently give a price upfront is in a much better position than those who can't.

5. Information sharing

BIM

"It can tell you how efficiently you're doing it or not. And there are people that have user interface designs that, you know, plug into some sort of computing system that draws out data from machinery. Of course, in advanced manufacturing sense, there's usually a computer-graded integrated system, which helps control machines for the production of building elements like cross-laminated timber. And I think what's coming out of this is using the various technology platforms such as blockchain, that link hardware sources together, and then have a distributed way of, managing information exchange is really where the technology is starting to move forward. BIM is another concept which really looks at taking internet of thing items and bringing them together in a coordinated way, much like a concert and a conductor to fashion the way that buildings are delivered"

Dr Paul Kremer. Season 3 Episode 18.

I used to have a colleague who was one of the hardest workers I've come across. He put his hand up to run 6 different projects and was a killer at his job. However, as it goes, 4 deadlines for drawings for construction arrived at a similar time. During that week he was working like a maniac. And when the other 2 projects called requesting for information, they were put on the backburner. The phone rang through straight to the keeper and understandably, the person on the other end of the phone wasn't happy.

The information doesn't always flow freely. Some times it's hard to get someone on the phone or organise a meeting to work the important and urgent details. Sharing information in a live fashion, for the design team or the supplier, using BIM or blockchain technologies can stop the unnecessary red lights that come when working collaboratively on a project.

Virtual Modelling

"We took all the pieces and we virtually modelled how that installation plan we'd go in on a time to delivery on the virtual model. They could see what we were talking about immediately. And two would allow them to actually understand their schedule right down to the labour detail, which I think is really fascinating because it's one of the loss communication skills. We usually, know exactly where everything's going, but we don't translate that conversation down to the people who are actually doing all the work. By doing a virtual model, we didn't have to have daily briefs to that level of detail. Now they could actually see the daily brief because it was day one, two, three, four of that cycle. So it really helped communicate that right down through everyone, right down to the guys that were cleaning up the site at the end of the day."

Karla Fraser, Director at Hive Constructions. Season 3 Episode 11.

Training of staff. Looking at drawings compared to every nut and bolt. Simpler QA checks. Experimentation with a build order. Introduction of new, or positioning of cranes. By building it in the boardroom with a virtual model, you can play with all sorts of things upfront ensuring building and installation efficiency.

6. Working with next-generation computational design

"A good friend of mine was the head of research and they worked on machine learning software that laid out desks in an office space. It's obviously what they do is quite narrow. They rent buildings and then try and put as many desks as they can in in each room. For an architect to work out whether they can fit six or seven or eight or 12 desks is a fairly, laborious thing and not particularly exciting or pleasant. So that's somewhere where software machine learning can step in and take over that task from a person. And that frees them up to do other much more interesting things. I think that sort of future for engineers and architects, cost consultants and people like that software will begin to take over those sorts of things that you find fairly dull and tedious in your day-to-day job that you have to do, but you don't necessarily love doing it. That's where I think we'll see the real gains. That's where it'll be interesting that that sort of task that might take you a day to do would just be done in, in a few seconds and reliably."

Richard Maddock, Associate Partner Foster and Partners. Season 3 Episode 2.

Most people think computational design is wildly speculative. However, one way to see its potential is to look across industries to see what sort of problems machine learning is solving.

Take driverless vehicles. A car with autopilot, driving from your home to the local milk bar. Vision is an extremely difficult concept to solve with computations. It needs to answer to the thousands of intricate situations us drivers take for granted when we hop in the driver's seat. And compare that to the scenario where I take an Adam Jones newton from the point loads generated by my chair. Firstly, it hits the floor system, onto the beam, onto the columns, transitioning through other floors as it makes its way to the foundations with only a handful of failure mechanisms. From my own perspective, if I compare the path of an Adam Jones newton to that of a Tesla, or Waymo vehicle making its way through the complexity of the roads; engineering design difficulties aren't in the same ball-park.

As Richard points out, computational design leveraging parametric design tools can take away the tasks that previously took days and turn them into seconds. This enables a dichotomy in design, where both extreme complexity and simplicity seem to make sense. Complexity in design is enabled with specialized and material-efficient that wasn't possible with hand computations. The Swatch headquarters by Shigeru Ban Architects provides just one example.

Image from: 'The Architect's Newspaper'

7. Work with the robots

"In the automotive industry where you are in the car line, you have the robots that are hard-coded doing tasks from predefined programs, that are optimised in different ways to construction. We have to read every drawing, interpret the drawing, assign data and create programs as we go."

Ola Skoglund, Chief Operating Officer Randek. Season 2 Episode 5.

The dichotomies are also apparent with robots. On one hand, they offer the ability to design a new type of building like Swatch Headquarters with over 2500 unique grid shell elements.

On the other, as Ola points out, the key to working with the robots for efficiency is to narrow their scope in order to have repetitive tasks. As the complexity of the structural system increases, the ability of the robot to be used to capacity diminishes.

8. Convergence

As Peter Diamandis pointed out in his book 'The Future Is Faster Than You Think', convergence could be the real driver of new Blue Oceans.

Converging factors mentioned above can combine in a positive feedback loop like waves to cause a "tsunami of innovation". For example, when you create a cocktail mix of designing to a supplier's parameters, computational design from engineers, with advanced robotics from the manufacturers, you stumble upon opportunities that have never been accessible to previous generations.

In Summary

Thanks to all those who've been on the Timber Talks podcast who have contributed their ideas into the ether, and have eventually made their way into this article. There has never been an exciting time to be a young person in construction. There are clear issues to be solved, whether for sustainability or innovation, and now a seemingly clearer line of sight for solving them. Much of this might be speculation but new design approaches are already cost-competitive, on the way to 'Cross The Chasm' to widespread adoption. With the Blue Ocean opportunities outlined above, the future looks bright.

Let me know what you think, whether you agree or disagree with these drivers in the comments below.

You can listen to the WoodSolutions Timber Talks Podcast here.

Urban development in a post-COVID market: an opportunity for mid-rise timber?

23/11/2020 9:15AM

Author: Laurence Ritchie, Cost & Program Estimator, WoodSolutions MAP

Laurence Ritchie of the Mid-rise Advisory Program delves into the opportunities for tall timber buildings in Australia’s post-COVID development market.

Timber construction has taken the Australian property sector by storm in recent years, with major institutions striving to walk the walk of sustainable development. This trend has recently taken a serious foothold in the mainstream with a 50 storey composite structure proposed for central Sydney by a partnership of Atlassian (developer), BVN and Shop Architects (architects), TTW (engineer), and Built (builder). However, quickly changing market conditions and external influences may lead one to wonder if this is the best development model for timber construction in the future? Read on to find out more.

In this post, the first of the WoodSolutions Mid-rise Advisory Program’s online blog, we will take a closer look into the primary opportunities for mid-rise timber buildings in Australia’s post-COVID urban environment. Drawing on the lived experience and expert knowledge within the WoodSolutions Mid-rise team as well as data and analysis from respected third parties, this post considers the potential impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic on the workforce and how this may reveal an opportunity for mid-rise timber construction.

Mid-rise timber construction is well and truly here to stay, with dozens of significant timber buildings now operational around the country and both local and international supply chains able to supply at a commercial scale and on commercial terms. These supply chains have been busy, with multiple major timber buildings of four or more storeys now either built or at late planning stages across the Country. While this development has taken place over the last decade (with much of it in the last 3-4 years), the current COVID-19 pandemic promises to disrupt the status quo, potentially for the long term.

The local pandemic management strategies have seen approximately 1/3 of Australia’s employed population transition to working from home, compared to just 12% (roughly 1/8 of the working population) before March 2020. A key tactic in reducing the spread of the Coronavirus, for many the forced time working from home has changed attitudes to work. Instead of commuting every day, 60% respondents to a recent survey of 1,100 office workers suggested they would prefer to continue to working from home for 2-3 days per week, even once restrictions are eased and some level of post-COVID normality resumes.

So what does this mean for planning, development, and timber construction?

A partial migration of the workforce from CBD desks to home offices presents a raft of new opportunities and challenges for the whole economy, but we’ll focus on the development impacts here. For the sake of this post we’ll divide development into two sectors: residential, and office.

In the residential sector, a shift to increased remote working means flexibility for many office-based staff. As long as they have a steady internet connection, office-workers can often effectively operate regardless of their location. Before we all start looking at beachside or rural properties though we should note that a longer term preference to spending a few days in the office per week for meetings, workshops, and other activities benefiting from in-person contact may require us to reside within a commutable distance, even if it’s further from the CBD than in pre-COVID times.

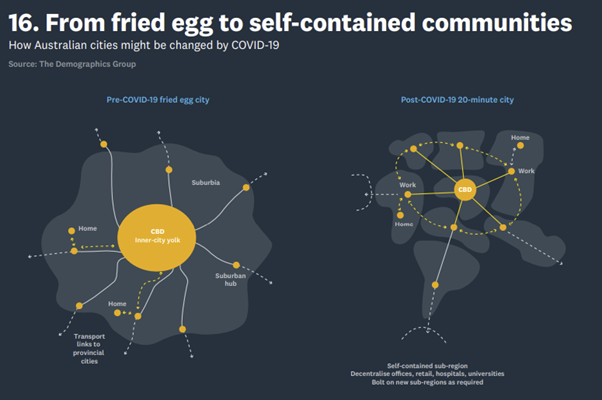

In this context it is realistic to expect that coming years may see much of the previously inner suburb and CBD based population move further from the city in favour of larger properties (whether apartments or detached) and less pollution, often for the same price or less. Rather than Australia’s traditional urban structure of a single highly congested central business district surrounded by a sea of under-populated housing (the ‘fried egg’ in the graphic below), the working from home landscape sees much of the once city-bound traffic stay closer to home, resulting in a stronger suburban economy. This concept – also championed by Bernard Salt of The Demographics Group - aligns well with the long-discussed ’20 minute city’ vision in which one’s residence, workplace, regularly visited shops, and other facilities exist within 20 minutes travel of each other.

But what does this mean for residential development? Firstly, new home design will change. People working from home will demand a dedicated work space, free from distraction and capable of fitting an ergonomic chair and/or standing desk. In practice this means that homes will increase in size, or at the very least will see previously unused spare bedrooms converted into regularly visited home offices. Improved acoustic separation may be a highly sought-after feature of these spaces, but at minimum some form of physical separation will be required.

While many may seek out a detached dwelling with a garage gym and enough garden for a veggie patch, a portion of the population more accustomed to apartment living (or simply wishing to avoid the maintenance of a larger detached home) may instead opt for town-homes, or even generously sized and conveniently located apartments. This is a clear market opportunity for mid-rise timber construction, where high quality residential units can be built at speed and with minimal disruption to the neighbours (who will probably be working from home throughout the build).

The office sector has also seen major changes throughout 2020. With the workforce ordered to work from home for much of the year, the normally teeming CBD environment was rendered dormant for several months. As restrictions now ease some life has returned, however the mass experiment of working from home has demonstrated the workforce’s ability to maintain productivity without an office, rendering an expensive CBD tenancy less appealing to many.

Companies currently renting expensive city-centre offices now have three options:

- They can change nothing, maintaining their existing office tenancies,

- Realising a reduced demand for desks they can downsize, or

- They can relocate to a new, more convenient and cheaper office in the suburbs, closer to their employees.

All three of these options are likely to be actioned by various employers, however the real opportunity for timber lies within the third. Companies following this path will drive an increase in demand of suburban offices and flexible working spaces, leading to a raft of new suburban office projects. These buildings will be limited in height by local codes, resulting in a prime opportunity for mid-rise timber development.

While this post indulges in some speculation, survey data and informed analysis aligns with the key assumptions around working from home and the future of our workplaces. While only time will tell the evolution of our urban landscape, it is clear the lived experience of the office-based workforce throughout 2020 will have lasting impacts. These impacts may result in a reinvigorated and refuelled market for suburban mid-rise construction, a perfect fit for timber construction systems.

If you have a question about this post or would like to learn more about designing or building with timber you can contact Laurence and the rest of the Mid-rise team here, or by email at midrise@woodsolutions.com.au

References:

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Household impacts of COVID-19 Survey. Retrieved from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/latest-release

Siebert, B. (2020). Coronavirus has forced Australians to work from home, but what are the impacts on CBDs?. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-18/coronavirus-working-from-home-impact-on-australian-cities/12435248

Ziffer, D. (2020). Most workers want ‘hybrid’ of home and office after coronavirus, study finds. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-23/most-workers-want-hybrid-of-home-and-office-post-coronavirus/12381318

Xero Australia and The Demographics Group. (2020). Rebuilding Australia: The Role of Small Business. Retrieved from: https://www.xero.com/content/dam/xero/pdf/rebuilding-australia-the-role-of-small-business.pdf