Publications

TBC

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) structures rely on well-designed connections to ensure structural performance, fire and acoustic integrity, and buildability. This guidance provides a technical overview of common CLT connection types and detailing considerations.

TBC

Joining one CLT panel to another (in the same plane) can be achieved with several joint profiles. The choice of joint affects structural capacity, fabrication complexity, and performance under fire or sound transmission. Common panel-to-panel joints include cover-board (surface spline) joints, half-lap joints, as well as spline or tongue-and-groove profiles and simple butt joints:

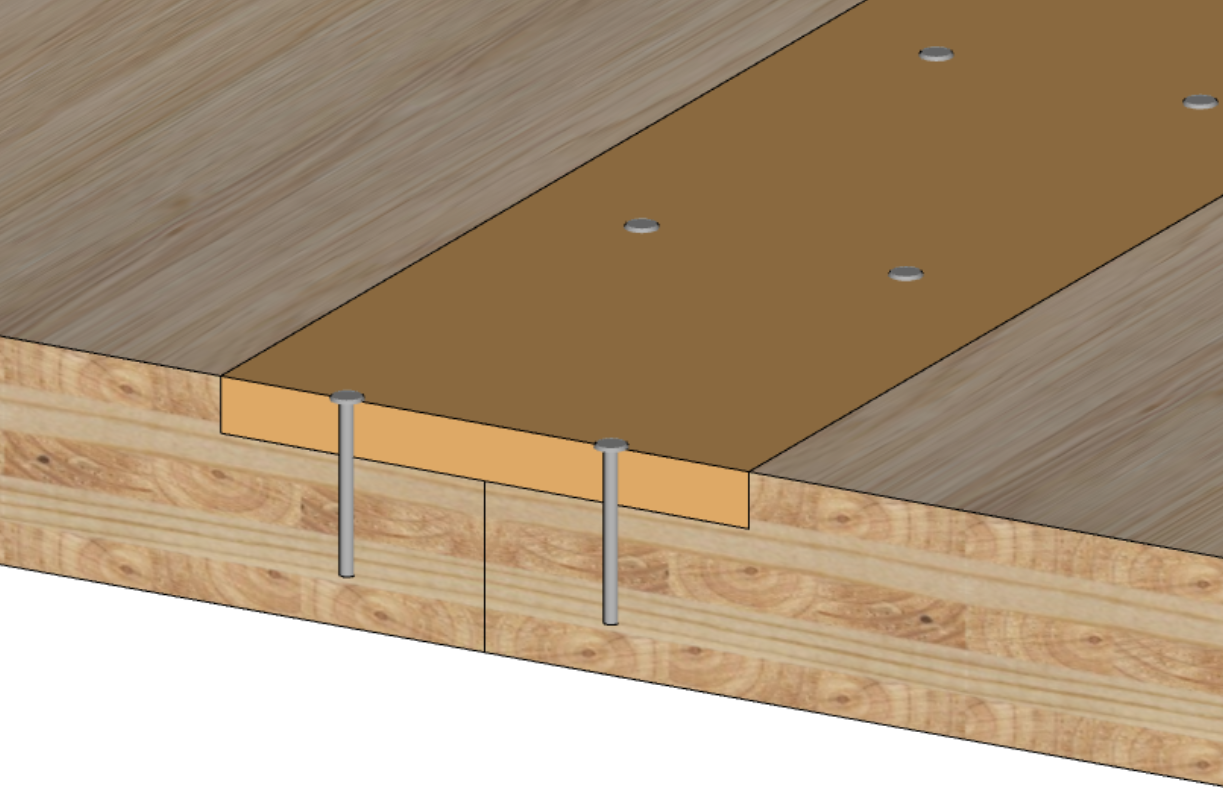

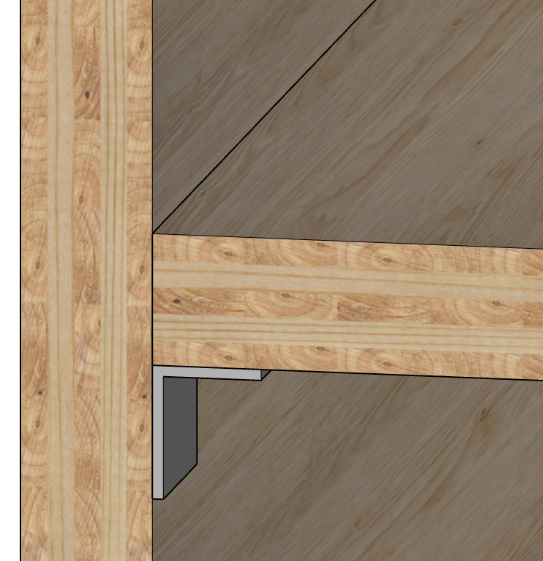

This joint uses a secondary piece (often plywood or LVL) fixed across the panel seam. A shallow rebate is pre-cut along the meeting edges of each CLT panel, and a strip (“spline” or cover board) is inserted or attached on site, spanning both panels. Typically nailed or screwed in place, the spline ties the panels together and provides in-plane shear transfer.

Figure 1: CLT Spline joint

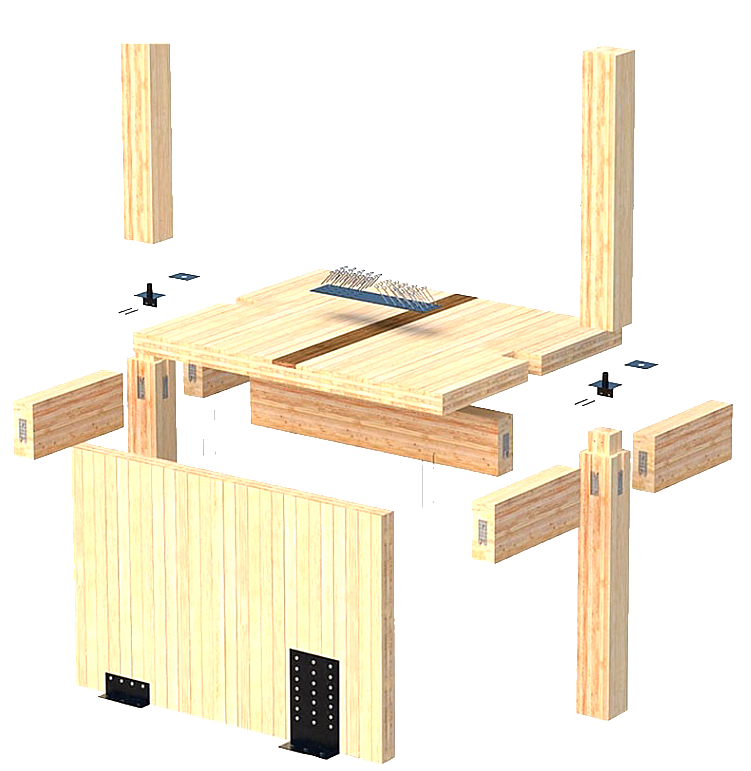

In a half-lap joint, each panel end is milled to half its thickness (generally) over its length so that overlapping panels interlock. Panels are typically secured through the lapped portion with self-tapping screws for both shear and uplift capacity. They are often used in long wall panels or at diaphragm joints requiring high uplift resistance. Half-lap joint designs are typically governed by edge distance requirements for the screws. Where high forces are expected at a half-lap, angled screw reinforcement may be added to prevent splitting of the timber.

Figure 2: CLT Half-Lap joint

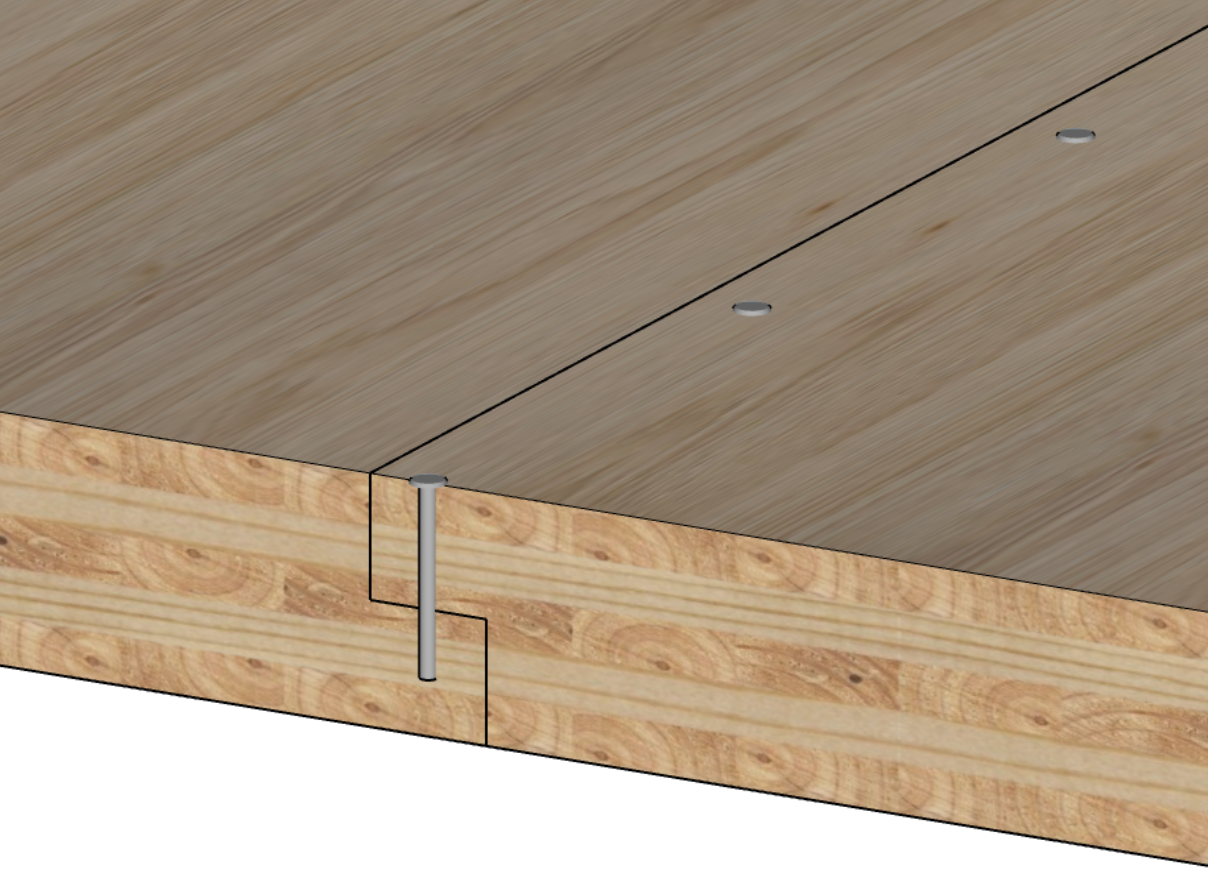

The simplest panel joint is a square-cut butt joint, where panels meet end-to-end with no overlap. Butt joints have no inherent strength or alignment and rely entirely on connectors like screws, nails, steel plates or brackets to transfer loads. Butt joints are generally only suitable where loads are low and other methods (lap or spline) are impractical.

Figure 3: CLT butt joint with mechanical fasteners

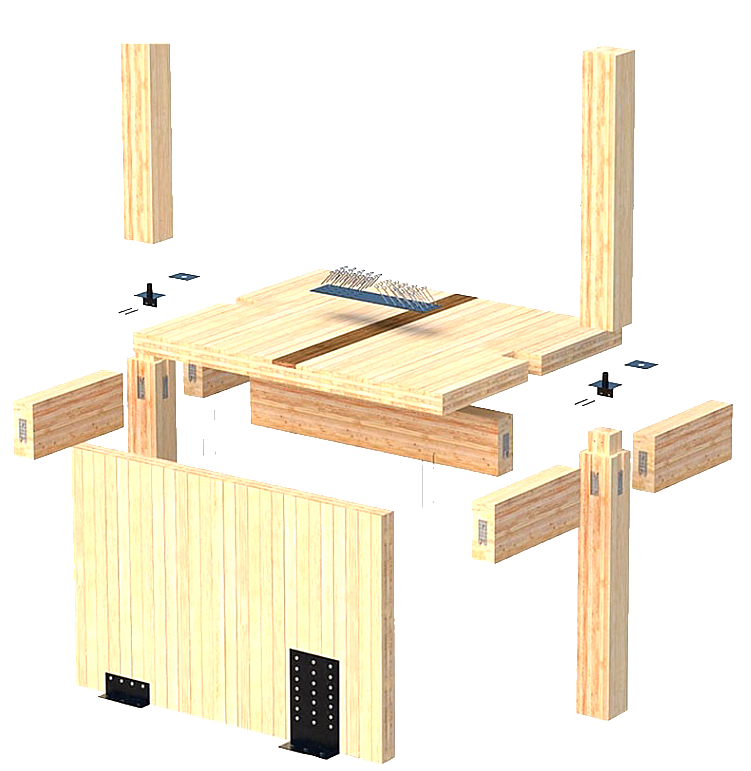

Connections between floor panels and supporting walls must transfer vertical loads, provide diaphragm action, and resist uplift or sliding in events like wind or earthquake. Two construction approaches are common for multi-storey timber buildings:

Figure 4: Platform construction

Figure 5: Balloon construction

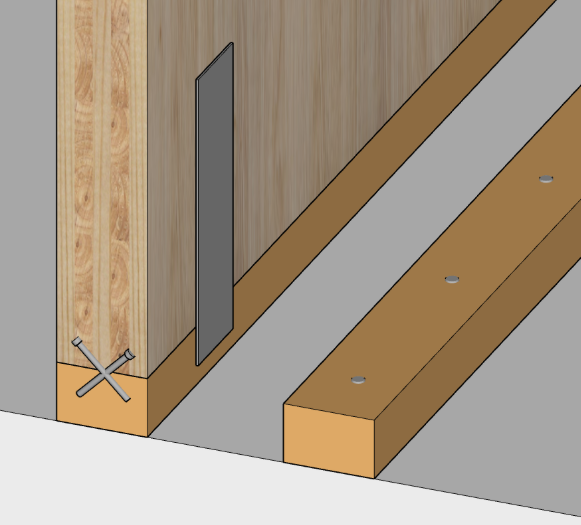

In platform systems, floor-to-wall connections occur at each floor level, whereas balloon framing involves floor panels hung off the side of a tall wall panel. In either case, secure fastening and proper sequencing are critical. Platform construction is generally preferred due to its simplicity, however care must be taken to account for the strength, stiffness and compression of the CLT panel between the walls. Balloon construction is generally seen when CLT floor panels meet continuous concrete walls of the core. In platform construction, the CLT wall panels of a lower storey act like a sill for the floor panels of the next level. The simplest detail is a direct bearing with screws driven from the floor panel down into the top of the wall. Angled self-tapping screws can provide both vertical load transfer and tie-down resistance. This screw-only detail is efficient and concealed, and is commonly used as the primary connection in platform CLT. For additional shear capacity or redundancy, steel angle brackets are frequently added at intervals along the wall-floor. These L-shaped brackets are typically fixed with screws into the CLT panel and anchor bolts into the wall/foundation or adjoining panel. Proprietary CLT angle brackets are rated for panel connections and can be selected based on required shear/tension capacity. Brackets are usually installed on the interior face of the wall (or concealed in false floors/walls) to maintain a clean exterior and protect them from fire.

In balloon construction (less common with CLT but used in some shafts or tall walls), the floor panel is connected to the side of a continuous wall panel. Here, hangers or ledgers may be used: e.g. a steel bracket or a wood ledger is attached to the wall, and the floor panel rests on it and is screwed from the side. Balloon configurations still need hold-down connectors at floor levels to tie the wall, but they allow walls to span multiple floors without horizontal joints. The decision between platform and balloon affects detailing: platform joints are easier to seal for fire/acoustics (floor sits on full wall thickness), whereas balloon walls avoid discontinuities in wall strength but require more complex floor hanger hardware.

Figure 6: Mjøstårnet’s construction showing the choice to use balloon framing for the core

Figure 7: An illustrative example of platform framing, concrete anchors, damp-proof-membranes, and temporary bracing

At the base of the ground-floor walls (or any CLT wall bearing on concrete or steel), it is good practice to introduce a sill plate or continuous sole plate. A timber sill (often a treated timber plate) between CLT and concrete:

Figure 8: Wall plate on the concrete level

The bottom of any CLT wall must not bear directly on concrete without a separation; a damp-proof course or membrane is also placed to prevent moisture ingress. Hold-down anchors or brackets are then used to tie the wall to the foundation through this sill. In many cases, standard heavy-duty hold-downs (used in light timber framing per AS 1684) or epoxy-set anchors can be adapted to CLT – the panel’s thickness and layer orientation should be considered for anchor design. Each project should specify the wall-to-floor panel connection method and spacing; suppliers often have tested details for these (e.g. screws at certain spacing, specific angle brackets, etc.) to achieve shear and uplift capacities.

Wall-to-wall connections occur in two contexts:

These joints must provide stability, transfer shear, and maintain alignment of panels, all while preventing gaps that could compromise acoustic, fire, or air barriers.

Vertical stacking (multi-storey walls): In platform construction, an upper storey wall sits atop the CLT floor slab which in turn bears on the wall below. The connection between wall panels of successive floors can simply be the floor diaphragm itself (platform approach) – i.e. the walls are not directly touching. However, when needed (e.g., for load transfer or alignment), a vertical wall splice can be introduced. One common detail is using short lengths of embedded threaded rod. steel plates or steel dowels projecting from the top of the lower wall into pre-drilled holes in the wall above (acting like alignment pins and resisting shear). More straightforwardly, installers often use long timber screws driven at an angle from the inside face of the upper wall panel down into the edge of the lower panel (through the floor thickness) to secure the stack. Another effective solution is a timber cleat: a dimensional lumber or LVL piece is let into a pocket or the gap between outer lamellae at the top of the lower panel, and the upper panel is positioned against it. The cleat is screwed to both panels, locking them in line. This cleated wall joint hides hardware and provides a positive shear transfer without external steel. It also simplifies erection by automatically positioning the upper panel (the cleat works as a guide). When stacking panels, ensure no direct wood-to-wood contact with continuous vertical joints across floors unless proper fire/acoustic detailing is in place; often a strip of fire-rated sealant or mineral wool is placed at the interface for fire stopping if required by the design. Manufacturers may have proprietary metal connectors (such as half-lapped steel plates with screws or concealed pins) for wall stacking – always follow tested details for any wall-to-wall panel connector to ensure it meets the required resistance (including fire if relevant).

Horizontal joints in walls (panel splices and corners): CLT walls longer than the transportable panel size are made by joining multiple panels along their vertical edges. These vertical panel-to-panel wall joints often use similar profiles as flat panel joints: half-laps, splines, or butt joints with screws. For a straight wall run, a half-lap joint can be milled at the vertical edge of two panels, then screwed together, creating a flush exterior. This is structurally effective and keeps panels aligned, but like the half-lap floor joint, it requires double-sided machining and reduces section at the join. Internal splines are a convenient alternative: a groove is routed full-height in the meeting edges and a plywood or LVL spline inserted, with screws or nails through the panel into the spline. This maintains full wall thickness externally and is easier to fabricate (groove from one side of each panel). If panels are just butted, steel plate connectors (e.g. flat plates or straps) can be recessed across the joint and screwed, or external steel knuckle plates can be used, but external plates may conflict with finishes and fire requirements. Thus, concealed solutions (like splines or half-laps with screws) are preferred for wall splices in CLT construction.

At corners and intersections, special care is needed to ensure a tight fit, even small gaps at a corner can let through noise or fire/smoke. A simple butt joint where one wall abuts the face of another is easy, but may open up over time as wood shrinks or if not perfectly flush. Alternatively, a steel angle bracket concealed at the corner (inside face) can tie the panels together, but the wooden half-lap corner generally offers better fire resistance and aesthetics. For T-intersections (where an internal wall meets a face of another), a cleated joint is effective: a vertical timber cleat or strip is attached to one wall panel and fits into a notch in the intersecting panel, then screwed from both sides. Applying screws directly through the ‘T’ is also advantageous. This is analogous to the cleated splice and provides a solid connection without external plates. Regardless of method, all wall joints should be detailed to prevent through-gaps. Use compressible foam gaskets or sealant in the joint as needed to ensure an airtight and sound-tight seam once assembled (more on sealing below). It’s also wise to stagger vertical joints on adjacent walls in multi-storey corners for stability (avoid a four-way joint lining up through floors).

Sealing panel joints and edges is crucial for acoustic privacy, moisture protection, and fire resistance. CLT panels themselves are massive and airtight, but the joints between panels can be weak points if not properly detailed. Even a few millimeters of gap can allow sound leakage or create a path for water and smoke. As such, design and construction should include measures to seal or cover these gaps as part of the detailing.

Figure 9: Gap seal within a CLT half-lap floor joint

Acoustic sealing: In multi-residential or office buildings, joints in floors and walls must be sealed to meet NCC acoustic performance targets. Flanking noise (sound bypassing through structural gaps) can severely undermine the sound rating of a CLT wall/floor assembly. To combat this, installers often apply acoustic sealant beads along panel joints (e.g. at floor perimeters and wall-to-wall joints) to create an airtight seal. These sealants are typically non-hardening, flexible caulks that maintain the seal as timber shrinks or moves. For example, a bead of acoustic-rated sealant between floor panels before screwing them together can improve airborne sound insulation by preventing airflow through the seam. Similarly, elastomeric gaskets or tapes are sometimes used: compressible foam tape can be applied to panel edges (especially around floor panel perimeters or door/window cutouts) so that when panels are installed, the foam compresses and seals the gap.

Research has shown that inserting thin elastomer interlayers in CLT joints can significantly improve acoustic isolation by dampening vibrations and blocking air paths. WoodSolutions Technical Design Guide 44 (CLT Acoustic Performance) provides tested floor and wall assemblies, noting that careful detailing, including sealing of joints, is required for compliance with NCC sound transmission class requirements. In practice, designers should specify all interface sealing requirements on drawings (e.g. “Apply continuous acoustic sealant at all panel-to-panel junctions in party walls and floors”). On site, quality control is needed to ensure sealants or gaskets are installed as specified prior to panel closure. A well-detailed CLT floor or wall, with sealed joints and appropriate insulation layers, can readily meet or exceed NCC acoustic separation criteria.

Moisture and air infiltration: Many CLT projects feature exposed timber surfaces, but one must still provide a continuous weather seal on the building envelope. Joint sealing plays a part in the overall moisture management strategy. For exterior walls or roofs, weather tapes or membranes are commonly applied over CLT panel joints to prevent rain penetration during construction. For example, a self-adhering flashing tape can be placed over horizontal and vertical panel seams externally, before adding any cladding or facade layers. These tapes stretch and maintain a waterproof seal as wood moves. Some CLT suppliers offer proprietary split-release tapes that are applied to panel edges prior to assembly, then pressed into place over the joint once panels are together. In addition to tapes, sealant in the joint (as a first line of defense) can be applied. This forms a gasket that stops water and also air leakage. Air tightness is not only about energy efficiency but also moisture: leakage paths can carry moist air into the panel interfaces, risking condensation.

During construction, temporary moisture protection is important. Panels often arrive with a factory-applied edge sealant or coating to reduce moisture absorption. Still, exposed panel edges (especially end grain in wall tops or floor panel ends) should always be covered to avoid water seeping into joints and causing swelling. Once the building is enclosed, any moisture that did enter joints should be allowed to dry; designs should avoid trapping water in joints (for instance, don’t fill a joint with non-breathable material without allowing for drying). Gap size is typically controlled by manufacturer tolerances, but installers should ensure panels are pulled tight (using clamps or come-alongs). For fire resistance, gaps beyond a certain size may fail integrity criteria. As one source notes, panel-to-panel connections are often the weak point in fire tests. Integrity failure can occur if joints open and flames pass through. Therefore, detailing should place panel joints away from direct fire exposure when possible (e.g. spline or lap on the side not exposed), and fire caulking should be used to seal any inevitable gaps.

In summary, all CLT joints should be treated via profiling, sealants, gaskets, or tapes to be as tight and secure as the solid panel field, ensuring the building meets requirements for acoustics, weatherproofing, and fire safety.

Modern CLT connections largely rely on mechanical fasteners, especially engineered screws and steel connectors, to achieve strength and ductility. Key fastener types and methods include:

Long, self-drilling wood screws are the bread and butter of CLT construction. These screws (typically carbon steel with specialized threads and tips) can be driven into CLT without pre-drilling, even in large diameters (8 to 14 mm) and lengths up to 400–600 mm or more. They are used for a variety of connections: from panel-to-panel splices (e.g. screwing half-laps together) to angle-driven hold-down screws and reinforcement (like stitching panels to beams). Self-tapping screws have high pull-out strength and can take combined lateral and axial loads, which allows them to resist uplift while also transferring shear. Their versatility means many connections can be detailed with just screws at specific angles and spacing, avoiding the need for bulky steel plates. When designing with screws, one must account for the layered nature of CLT. If screws are loaded in withdrawal through cross-layers or gaps (from unbonded lamellas), design values are adjusted accordingly. AS 1720.1 (the Australian Timber Structures code) provides equations for dowel-type fasteners (including screws) in timber; however, engineers often use European yield models or manufacturers’ tested values for long screws in CLT. Embedment and withdrawal capacities should be verified from technical literature. A word of caution: fully threaded screws can act like clamps across wood elements, while beneficial for certain connections, they can restrain the natural shrink/swell of timber and potentially induce splitting if overused. It’s good practice to not overly constrain large panels with many fully-threaded screws in directions that restrain moisture movement. Screws can be used judiciously to prevent cracking, as well! The lesson is to work with the movement of your timber, not against it.

These include a range of connectors or all kinds, from right-angle brackets, flat straps, hold-down shoes, and concealed plates. Many are proprietary connectors specifically made for CLT or heavy timber. Angle brackets tie walls to floors or foundations, and come in reinforced varieties to handle high forces. Flat straps or plates are used to join panels in-plane (for instance, a steel plate screwed across a wall butt joint to resist tension). Knife plates (embedded steel plates with bolts or dowels) are common in GLT beam and column connections and can be used in CLT as well: concealed knife plates can connect a CLT floor panel to a glulam beam or concrete wall with the steel hidden inside a routed slot. Concealed two-part connectors (often cast steel or aluminum) are also available: these are installed in pockets in the two joining members and then mate on site. They can carry heavy loads (like column-beam connections) and keep metal hidden for fire protection. When using steel hardware in CLT, consideration must be given to fire and durability: exposed steel may need intumescent paint or covering to meet fire resistance, since unprotected steel connectors can cause premature failure in a fire-rated timber assembly. The NCC requires that if an element (wall, floor) has a fire-resistance level (FRL), its connections must not reduce that performance, hence, detailing often recesses steel plates and covers them with wood plugs or fire-rated sealant to delay heating. Corrosion protection (galvanizing or stainless steel) is also important if the connectors could be exposed to moisture in service or construction (refer AS/NZS 2699 or AS 3566 for appropriate coatings). It’s noteworthy that many connection systems (screws, plates, etc.) are proprietary, so designers should either specify performance or reference an approved product.

Traditional nails are not widely used in CLT structural connections, mainly because nails lack the withdrawal strength that screws provide. Nails may attach metal hardware like joist hangers or brackets to CLT where lateral loading governs. One must avoid driving nails into the narrow panel edges (end grain) for withdrawal resistance, this is generally prohibited by design codes. Timber rivets (multi-pronged metal spikes used in glulam connections) are rarely used in CLT. Bolts and dowels are widely used, particularly for steel plate connections. Bolted connections should consider the cross-layer layout, predrilling slightly oversize can prevent splitting, and surface steel washers/plates may be needed to distribute forces. Overall, bolts/dowels in CLT behave similarly to glulam, though the cross laminations can interrupt load paths.

Mass timber is rapidly evolving, with many creative minds attempting to solve problems and accelerate installation through clever approaches to connections. Various proprietary fastener systems exist. Glued-in rods are one example: steel rods epoxied into pre-drilled holes in CLT can create high-capacity connections with the steel entirely embedded. Some innovative firms are experimenting with on-site glueing only - no metal fastening at all. These have been used in Europe for moment connections or anchoring CLT to concrete, but require specialized design (not yet standardized in Australian codes). The KNAPP® system refers to proprietary metal connectors that snap together, useful for quickly assembling panels with hidden connectors. There are also self-drilling long coach screws and split-ring or shear key connectors occasionally used where very high shear must be transferred (e.g. timber shear walls to foundations). When using any proprietary system, ensure it has relevant technical approvals or test data (e.g. European Technical Approvals or CodeMark in Australia) to satisfy engineers and building certifiers. It’s also advisable to stick with systems familiar to local contractors or recommended by the CLT supplier, to avoid construction complications. As a rule, simpler is better. Many CLT buildings have succeeded with a palette of just screws, steel angles, and brackets for all connections. Some structures use timber dowels, and omit steel fasteners altogether. Often little more than screw heads need be visible if connections are well detailed, a testament to the efficiency of self-tapping screws and minimal hardware when properly applied.

Building with large prefabricated panels like CLT offers speed and precision, but it also demands good planning to accommodate tolerances and a clear assembly sequence. Below are best practices for installation and tolerances:

CLT panels are manufactured with CNC machinery, achieving very high dimensional accuracy, typically within a few millimetres over several meters. Major European suppliers, for example, often specify that their CLT panels meet DIN 18203-2 tolerance standards. This precision means that on-site fitting is mostly about aligning panels, not cutting or trimming. This means that site conditions (foundation accuracy, slab levelness, and moisture conditions etc.) play a significant role. Ensure supports are level and true before panel placement: a common tolerance is to keep level variance under ~5 mm across a panel footprint. Small gaps at the base can be taken up with shims or a grout bed under the sill if needed, but prevention is best. During erection, panels might have a slight bow or camber from moisture or manufacturing (especially longer panels). The Australian Timber Construction Manual or supplier guides may give limits (e.g. bow/span ratio). Typically, if a panel is out of flat by more than, say, 1/500 of its length, it should be assessed or adjusted. Overall, proper storage (flat, supported) and handling of panels helps maintain their true shape upon installation.

A clear sequence minimises handling of heavy panels, optimising crane time. Generally walls first, then floors. For a given storey, the sequence might be:

Because CLT floors act as diaphragms, it’s important to get them in place to stabilize the supporting walls below. Install teams often use temporary braces (e.g., adjustable steel props or timber struts) on walls until the floors are in and all connections tightened. Each panel usually comes with pre-installed lifting points or brackets: follow supplier guidelines on where to attach crane hooks, and always use the recommended lifting sling arrangement to avoid panel damage or imbalance. Panels can often be placed directly from truck to final position if sequencing is planned well for “just-in-time” delivery. Number or mark each panel according to an erection drawing so that the crew can identify which piece goes next.

Even with CNC precision, a small gap (2-5 mm) is typically designed in at certain connections to allow ease of fit and adjustment of creep, to prevent a continuous run of slightly oversized panels from compounding. (especially for joints involving panel overlap such as half-laps). Panels should never be forced with excessive pressure if something isn’t fitting – stop and check dimensions or obstructions. Often, a misalignment is due to debris or a slight rotation; using come-alongs (ratchet straps) or panel alignment bars can help pull panels tight together once roughly in place. Installers might use crowbars in pre-cut holes or specialized clamps that hook into panel edges to draw them together. Achieving tight joints is important, but it’s also recognized that wood can swell: if panels arrive at a lower moisture content (say 8%) and then gain moisture on site, they are very likely to expand as they reach Equilibrium Moisture Content. Contractors sometimes leave a small expansion gap (a few mm every few panels, or at perimeter) that is later sealed, to accommodate this. Any intentional gap should be according to the design (for example, some designs include a ~10 mm gap at floor diaphragm ends for seismic movement or to allow installation tolerance, then cover it with trim or sealant).

Multi-storey CLT buildings benefit from careful surveying. After installing a floor and the next set of walls, check that the walls are plumb and in the correct position relative to the grid (using total stations or laser levels). Minor adjustments can be made by shimming at the base or using the slack in screw holes of brackets before final tightening. The cumulative tolerance over several storeys should be monitored: if each level is off by 3 mm, by level 8 you have 24 mm which might affect facade connections, etc. The NCC doesn’t prescribe specific plumbness tolerances for CLT, but general practice might suggest walls should be within say 4 mm in 2.7 m for plumb and not more than ~10-15 mm out of position overall in a tall building. Because CLT panels are both structure and often finish, achieving a smooth flush alignment at joints is important for aesthetics too. Any slight steps at floor panel joints can be sanded or levelled with a skim (if exposed floor), but it’s best to place them flush initially.

Plan when to install connectors: many angle brackets or hold-downs can be partially attached to panels on the ground to reduce work at height. For example, screw an angle bracket to the bottom of a wall panel while it’s on the ground, so that after the wall is stood, the bracket just needs anchoring to the floor. However, ensure this doesn’t interfere with lifting. Installation guides from manufacturers often have step-by-step connection sequences. Also consider service penetration coordination: large openings for ducts or staircases might break the sequence (e.g., you might delay installing a particular floor panel until a piece of equipment is lowered through the top). Always coordinate with the crane operator about any special picks or rotations, as CLT panels can be sensitive to bending if lifted improperly.

During construction, unconnected panels or partially fixed panels must be braced against wind. A bare CLT wall (without floors or adjacent returns) can easily be caught by the wind; temporary screw connections or braces should be designed for wind loads if panels are going to sit exposed for extended periods. Also, if using panels as temporary work platforms, ensure they are secured and check if temporary propping is needed for long spans until all design connections are made. Follow recommended construction sequencing in resources like WoodSolutions Installation Guides or supplier manuals, which often outline the erection logic and bracing requirements.

Often 20-30% faster than traditional concrete construction, as industry case studies show, but only if tolerances and sequencing are proactively managed. The modified adage is “Model as much as required, measure twice, lift once.” By planning each lift, pre-checking dimensions, and having the right tools on hand to align and secure panels, the assembly will go smoothly and the structure will meet all the dimensional tolerances for finishes that follow.

Modern buildings often combine CLT panels with other structural systems – whether it’s concrete cores, steel frames, or glulam beams. These hybrid connections require careful detailing to account for the different material properties.

A typical scenario is CLT walls or floors connecting to a concrete slab, foundation, or core wall. The primary strategy is to use steel connectors anchored into the concrete and screwed or bolted to the CLT. For example, at the base of a CLT shear wall on a concrete foundation, one might cast-in anchor bolts that align with pre-drilled holes in a steel angle or plate, which is then attached to the CLT with screws. Proprietary connectors specifically for panel anchorage to concrete may be helpful. Alternatively, internal steel plates epoxied into the concrete can mate with slots in the CLT. Key considerations: include a moisture break (as mentioned, timber should be isolated from concrete by a membrane or sill plate), and allow for reasonable tolerances of the various materials: slotted holes or adjustable brackets can help accommodate misalignment in anchor bolts. In seismic designs, avoid overly rigid connections to concrete; using ductile steel connectors (that yield under extreme loads) will prevent the CLT from splitting. CLT diaphragms (floors) connecting to concrete cores often use embed plates in the core that screw to the CLT, or angle brackets on the face of the core. These connections need to transfer shear (wind, quake forces) into the core: shear keys or toothed plates can be considered if forces are high. Engineers should design these per AS 1720.1 and AS 3600 (concrete) combined, checking that the anchorage into concrete can develop the timber capacity.

When CLT panels interface with steel beams or columns, the connections often rely on steel-to-steel attachments coupled with timber screws. A common detail is a steel top flange plate: weld a flat plate on top of the beam, and drive screws down through the plate into the CLT panel acting as a ledger. Another approach is clamping the panel to the beam via angle brackets on the side of the beam, or self-tapping screws angled up from the underside of the CLT into the steel web (special screws exist that can tap into steel up to 5–6 mm thick). However, direct screwing into steel often requires pre drilling and is less common; typically a steel connector with bolts to steel and screws to wood is preferred. For steel columns connecting to CLT walls, knife plate connectors can be embedded: a plate extending from the steel column fits into a slot in the CLT panel edge and is bolted/doweled in place. This provides a moment-resisting or at least shear-resisting connection while keeping steel hidden (with wood plugs over bolt heads for fire). One must consider the differential movement: CLT may shrink slightly in thickness over time (and with moisture changes) whereas steel won’t - if panels are stacked between steel floors, vertical shrinkage of a few millimeters per floor could accumulate. Accommodate this in connection slots or adjustable support seats. Also, the stiffness mismatch means steel will attract more load if connected rigidly to CLT; often a bit of flexibility (long slotted holes or bearing pads) can relieve stress concentrations. For NCC compliance, note that steel members can get much hotter in fire than timber, a steel beam supporting a CLT floor might need fire protection, else the connection could fail even if the timber panel is fine. Designing CLT floors to simply rest on steel (gravity support) and relying on separate steel bracing for lateral loads is one strategy to decouple systems and simplify fire design.

It’s common to use glulam or LVL beams and columns together with CLT panels, as part of a gravity system or for long spans. Connections here are all-timber but often still use steel hardware. For example, a CLT floor sitting on a glulam beam can be connected with screws driven at angles through the CLT into the beam (a form of timber-to-timber connection). Multiple screws in a row can create a moment-resisting couple (not as rigid as a steel plate, but enough for diaphragm continuity). A hanger can also be used: companies make face-mount hangers for CLT-to-beam, similar to joist hangers but sized for panel thickness. When connecting wall panels to glulam columns, knife plates or exterior steel plates are used, or simple lag screws toe-nailed through the panel into the column. Since all members are timber, differential shrinkage is less of an issue if they have similar moisture content and orientation (though note, cross-grain CLT vs long-grain glulam will shrink differently in width vs depth). For heavy gravity loads (e.g., point loads of beams into CLT panels), bearing stiffeners or hardwood plugs can be inserted into the CLT to locally reinforce the compression zone. It’s important that loads from other timber elements be spread into the CLT’s layers appropriately, sometimes dapped joints or steel seat connectors are employed so that a beam bears on the CLT without crushing the surface layer.

CLT floor or wall panels work well alongside conventional light wood framing. Interfaces here might be at floor-to-wall joints where a timber-framed wall sits on a CLT floor, or vice versa. These can usually be treated like standard platform framing details, such as a bottom plate of a stud wall bolted to a CLT slab (the CLT acting like a rim joist), or a CLT wall anchored to a wood-framed floor via metal straps to the floor framing. Use coach screws or structural screws rather than ordinary nails if connecting into the side grain of CLT from light framing members.

Structural engineers should communicate expected movements (e.g. concrete creep, timber shrinkage, steel elongation in fire) to ensure details still perform over time and under extreme conditions. From a compliance standpoint, the National Construction Code (NCC) doesn’t prohibit mixing systems, but each interface must satisfy the relevant provisions for structure, fire, etc. For example, if a steel-to-CLT connection is part of a fire-rated wall, one must show it meets the integrity and insulation criteria for the required FRL (often via testing to AS 1530.4 or engineering analysis). Many suppliers and resources like have details for hybrid construction.

When designing and detailing CLT connections in Australia, it’s essential to reference the appropriate standards and ensure compliance with the National Construction Code (NCC). Here are key standards and code considerations:

Achieving compliance for CLT connections is entirely feasible. Numerous CLT buildings in Australia have been completed under the current codes. It relies on proper design to the intent of standards and sometimes creative solutions for fire/acoustic requirements. Always refer to the latest WoodSolutions publications and Technical Design Guides for reference details. Using proven details and ensuring they align with Australian standards will result in efficient, code-compliant CLT connections. As with any structure, clear documentation and engineer sign-off on all connection details is mandatory.