Publications

TBC

Timber is a versatile, beautiful material, with clever design evident at the connections. Unlike inert materials, timber moves. It expands and contracts with changes in moisture, and without considered connection detailing its surface can degrade. The choice of fasteners, joint types and adhesives plays a critical role in the strength, durability and visual appeal of a timber structure or fitout. It also directly affects how well a timber assembly can accommodate seasonal movement, resist corrosion and maintain its performance over time.

This guide sets out practical considerations for selecting and detailing:

By applying the principles outlined here, you’ll help ensure timber connections meet structural and durability requirements and enhance the overall aesthetic of your project.

TBC

Fasteners are the unseen anchors that hold timber projects together. From fine internal joinery to robust external structures, the type of fastener and the level of corrosion protection selected will directly affect long-term durability, aesthetics and compliance.

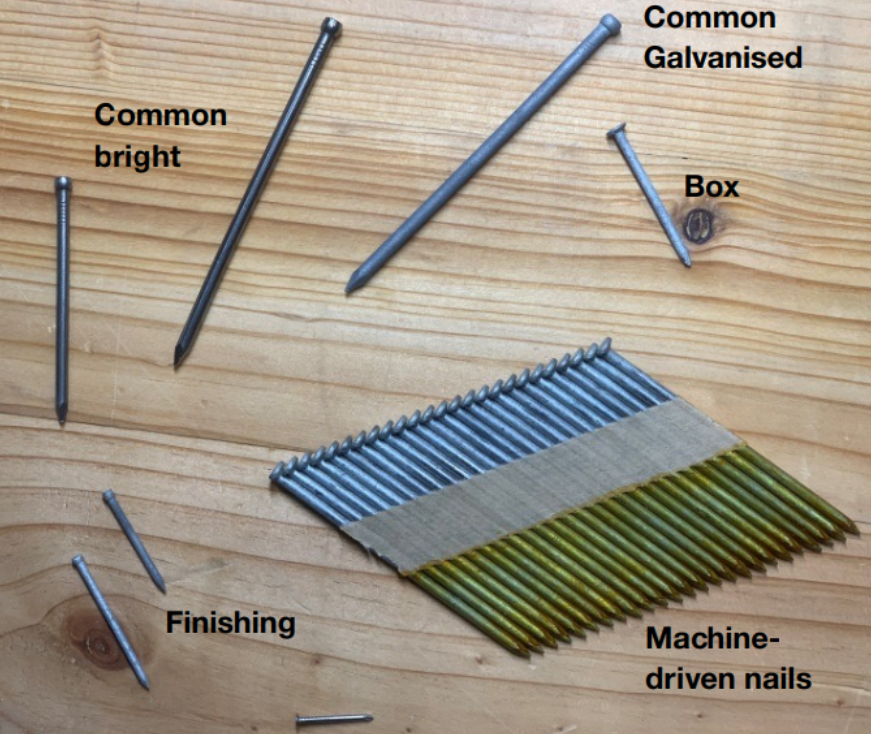

Figure 1: Range of common nails - TDG 52 p12

Nails remain one of the most widely used fasteners in timber construction. They are quick to install and suited to a wide variety of applications, from framing to fixing linings. Types include:

Common nails: thicker shank, ideal for structural framing (often skew-nailed).

Figure 2: Common nail

Box nails: thinner shank reduces splitting in thinner materials, though not for structural loads.

Figure 3: Box Nails

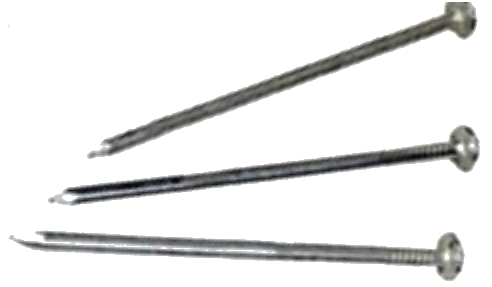

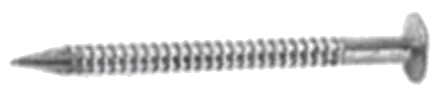

Annular (ring shank) nails: provide superior withdrawal resistance, particularly useful in softwoods and for decking.

Figure 4: Annular (ring shank) nail

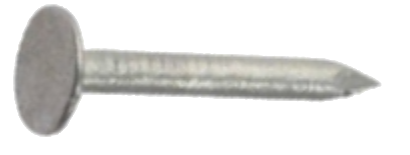

Clouts and framing bracket nails: used for sheet fixings and proprietary brackets.

Figure 5: Clout

Figure 6: Framing nail

Finishing nails & brads: for cabinetry and trim work, designed to be countersunk and concealed.

Figure 7: Finishing / Brad nails

Special types: duplex nails (temporary works), staples (non-structural sheeting), and corrugated fasteners (joining mitres in crates or lightweight joinery).

Figure 8: Duplex Head or Double Head Nails

Nails are often coated to increase the service life, the holding strength or aid in the driving of the nail. Vinyl coating of nails aids efficient driving and offers superior grip, but does not protect against corrosion. Nails can also be coated with cement or adhesive to improve their holding power. Most construction nails are steel, often with some kind of surface coating.

In the presence of moisture, metals used for nails may corrode when in contact with wood treated with copper-based preservative or fire-retardant treatments. Timber treated with ammoniacal copper arsenate or chromate copper arsenate performed well with nails made from copper, silicon bronze and 300 series stainless steel. However, timber treated with copper azole or alkaline copper quaternary requires 300 series stainless steel nails.

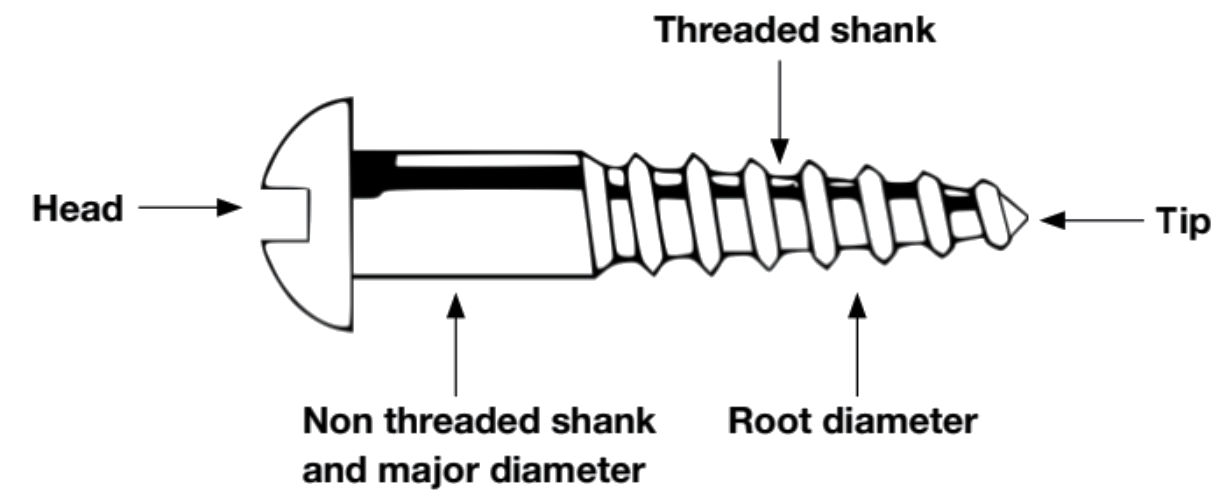

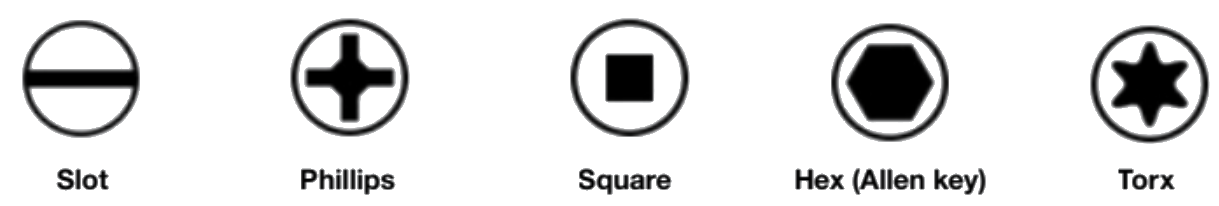

The principal parts of a screw are the head, shank, thread, and core. The root diameter, a standard reference to the size of the screw, is the thickness of the metal the thread is wrapped around, and is generally about two-thirds of the shank diameter. There are many aspects to specifying a wood screw: head type, drive type, shank width, thread length, location and point or tip. They are classified according to material, type, finish, the shape of the head and diameter or shank’s gauge. Gauge is an imperial measurement of the shank, still in common use today.

Figure 9: Features of a screw

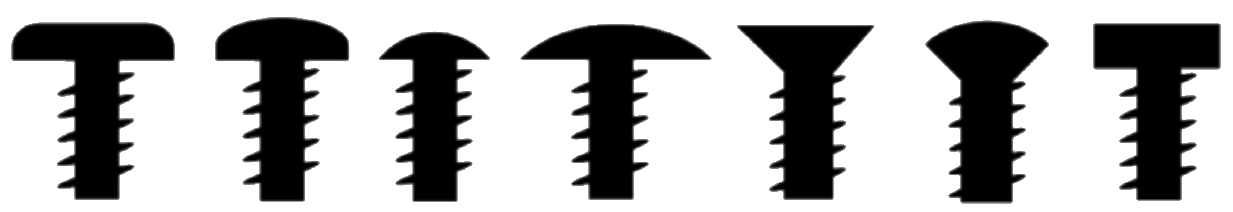

Figure 10: Screw Head Type, Left to Right: pan, dome, round, mushroom, countersunk, raised, hex

Figure 11: Common Drive Types

Require pre-drilled holes. They cut into the wood fibres for higher withdrawal capacity than nails (about 3x for the same diameter). Ideal for cabinetry and lighter structural tasks.

Self-tapping, high-strength screws that enable rapid installation without pre-drilling in softwood in some situations. They can be driven at angles (typically 45°) to significantly boost joint capacity, reduce splitting and act in both shear and tension. One key difference between modern screws and traditional screws is the relationship between thread diameter and shank diameter. The thread on modern screws protrudes above the shank providing a more effective thread diameter than the shank diameter. For traditional screws, the thread diameter is the same as the shank diameter. Modern screws designate their size according to the outer thread diameter, not the shank diameter as in traditional screws.

Adhesive-only or combined connections: especially for mass timber where glue lines, glued rods or combined adhesive/fastener systems are used.

The way timber members are joined together has a profound impact on the appearance, strength and service life of a structure. From traditional hand-cut joints to advanced engineered connectors, the selection and detailing of joints should always reflect the load requirements, exposure conditions and movement characteristics of timber.

Mortice and tenon, dovetail, lap joints and halving joints have been used for centuries. These joints rely on precise carpentry to transfer loads through interlocking timber shapes, often secured by timber pegs or glue.

Figure 12: Traditional scarf joint. Source: Heartwood Build

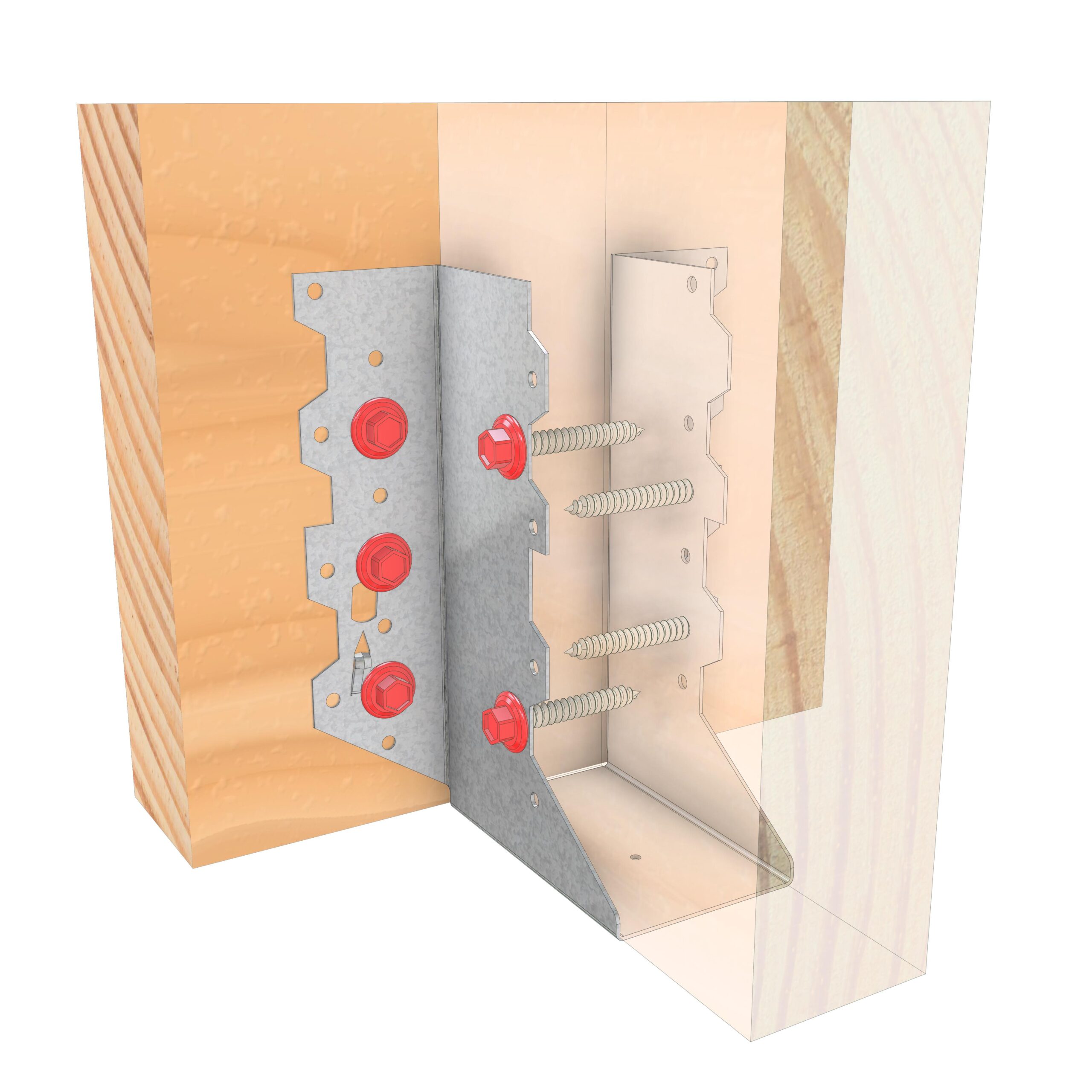

Contemporary timber construction increasingly uses metal connectors, screws, bolts and proprietary systems, which bring consistency and simplify construction.

Figure 13: Joist Hanger. Source: Pryda

Figure 14: Engineered timber connector. Source: Construction Canada

Many mass timber connections combine mechanical fasteners and adhesives to optimise stiffness, transfer loads smoothly and reduce creep. For example, CLT panels may be joined with a mix of screws and glue lines.

For cabinetry, doors, windows and other internal features:

These joints do not usually carry significant structural loads but must still accommodate seasonal timber movement.

Timber’s natural tendency to shrink and swell means joints need careful design:

Tables in AS 1720.1 specify minimum end, edge and spacing distances to reduce splitting risk - these are especially critical for joints under repeated loading or in unseasoned hardwoods.

Choosing the right joint type is about balancing:

Adhesives play a vital role in timber construction, whether enhancing the load-carrying capacity of structural members or achieving crisp, clean finishes in decorative joinery. The right adhesive choice improves performance, prolongs life and helps manage timber’s inherent movement.

Fun fact: Resorcinol is a key ingredient in phenolic resins, like one of the first common plastics, bake-o-lite.

Factory-controlled adhesives: CLT, LVL and glulam rely on industrial adhesives that meet rigorous durability standards (per AS/NZS 1328, AS/NZS 4357 or EN standards).

Timber must be well fitted, dust-free, and within recommended moisture content ranges (often 10-15%). Too dry or too wet can weaken bonds. Furthermore, shrinkage of members can limit the time between surface planing of timber components and glueing, especially for very stiff hardwoods and face glueing of boards.

Even the strongest adhesive is ineffective without adequate pressure during cure. Follow manufacturer’s guidelines - often requiring firm clamping for 20-60 minutes, and full cure over 24 hours.

Adhesives lock components together and may become stressed if the timber moves significantly due to humidity changes. Where possible:

WS TDG 52 (Section 5.3) highlights innovations such as:

These approaches demand high quality control, careful alignment, and often lab-tested systems to validate performance.

Timber is a living material that continues to respond to its environment. Its seasonal swelling and shrinking, combined with the demands of live and static loads, means careful detailing is essential to ensure connections remain strong and the structure performs as intended.

Moisture-driven movement: Timber expands across the grain as it absorbs moisture and contracts as it dries. Even a 1% change in moisture content can translate to measurable dimensional changes in wide members.

Bearing and shear

Withdrawal and tension

Reinforcement where needed

Using adhesives in conjunction with mechanical fasteners spreads loads more evenly and reduces stress concentrations. This is especially valuable in:

AS 1720.4 (referenced in TDG 52) notes:

The thoughtful specification and detailing of fasteners, joints and adhesives is fundamental to timber’s performance, appearance and longevity. Whether you’re working on a finely crafted interior fitout or a robust outdoor structure, taking time to match connection methods to the timber species, expected loads and environmental conditions pays dividends over the life of the project. By:

you’ll ensure your timber designs stand the test of time - structurally sound, visually appealing and built to endure Australia’s diverse conditions.