Publications

TBC

Measuring the moisture content (MC) of timber is one of the simplest and most powerful ways to safeguard durability, compliance, and structural performance on-site. Yet it is often treated as a low-priority task until problems arise. Choosing the right measurement method, and interpreting the results correctly, is essential for preventing costly defects caused by shrinkage, swelling, decay, or loss of structural capacity.

This guide explains how different moisture measurement methods work, when to use them, and what level of accuracy they offer. It also outlines how to interpret readings across species, climates, and applications in accordance with NCC 2022, AS 1684, and AS/NZS 1080.1.

TBC

Accurately measuring timber moisture content is often overlooked. Understanding how to measure and interpret the moisture content of timber is an on-site superpower, and is fundamental to compliance, durability, and structural performance. Timber is hygroscopic, constantly exchanging moisture with its environment.When installed outside its target range, or when its moisture content changes significantly in service, it can lead to dimensional movement, surface checking, decay, or even structural failure.

Monitoring moisture is therefore both a compliance requirement and a performance safeguard. NCC 2022 and AS 1684 Residential timber-framed construction specify that seasoned structural framing must not exceed 18 % MC at the time of installation, while appearance or mass timber elements generally require lower values (typically 10-16 % MC) to minimise movement and surface defects.

Moisture measurement plays a key role at four critical stages of a project:

In practice, choosing the right measurement method ensures reliable results that can be acted on with confidence. This guide explains the different methods available, their accuracy, and how to use them correctly.

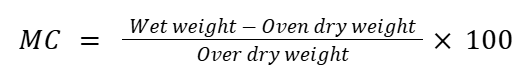

Moisture content (MC) is the ratio of the mass of water in a piece of timber to its oven-dry mass, expressed as a percentage. It is defined in AS/NZS 1080.1 Timber - Methods of test - Moisture content as:

This simple relationship underpins almost every compliance and performance check in timber construction.

This measure underpins all compliance checks. For example:

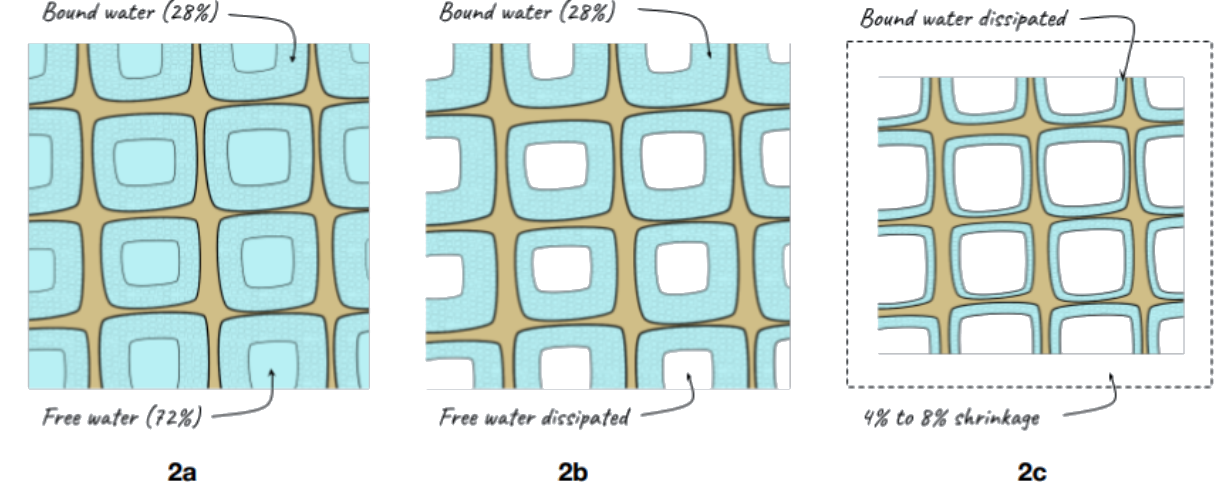

The Fibre Saturation Point is the threshold between “free water” and “bound water” in wood.

Most moisture-related movement occurs as timber cycles between the FSP and its equilibrium with ambient conditions.

Figure 1: Fibre saturation point in wood cells

The EMC is the point where timber is neither gaining nor losing moisture relative to its environment. That is, the timber has reached a state of equilibrium with its environment and is no longer undergoing any consistent directional change in moisture content (small diurnal and seasonal variations are expected). EMC varies by climate and exposure:

EMC is the benchmark against which field meter readings should be interpreted. It is also the target moisture level timber should reach before installation. Installing material significantly above or below local EMC leads to swelling, shrinkage, and distortion as the timber adjusts to its environment.

Accurate understanding of these baseline concepts allows the correct interpretation of readings from any measurement device.

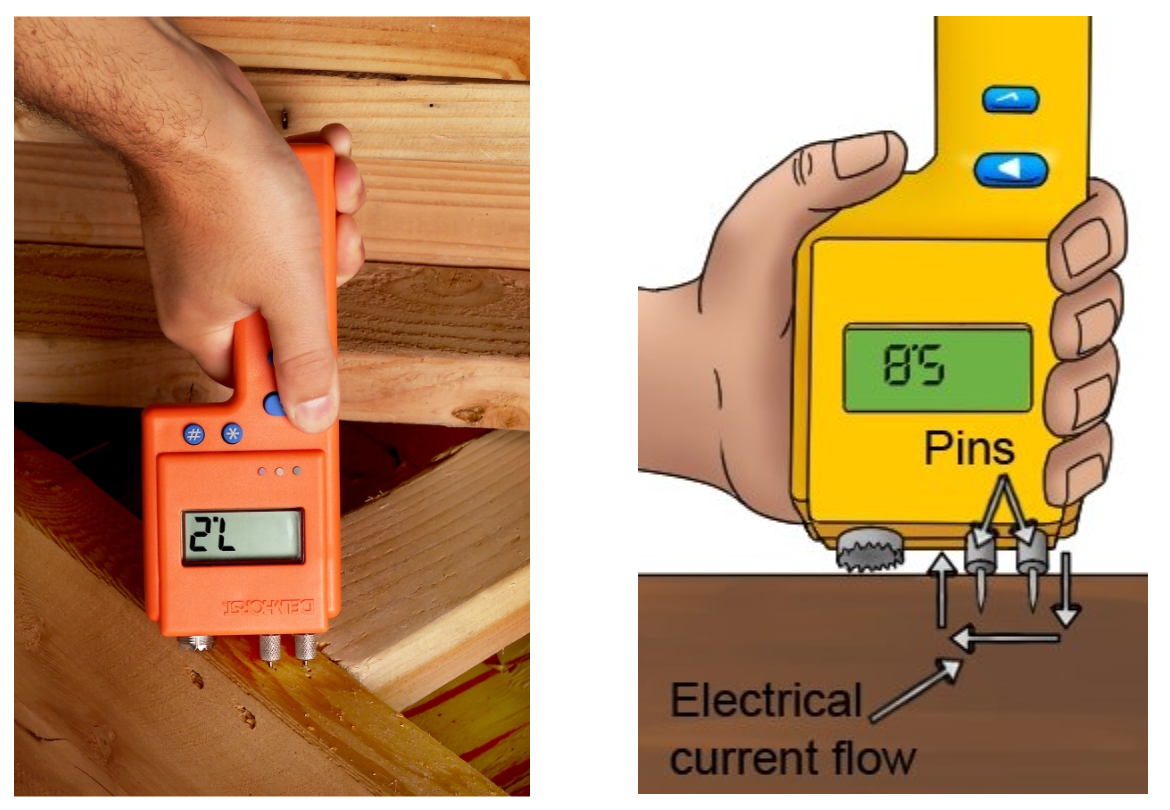

Resistance meters measure electrical resistance between two insulated steel pins driven into the timber. Because dry wood is a poor conductor, resistance falls sharply and predictably as moisture increases. The meter converts this resistance into a percentage moisture content, usually calibrated against oven-dry test data from AS/NZS 1080.1.

Figure 2: Use and mechanism of pin-type moisture meters

Every resistance meter should be used with the manufacturer’s correction tables or digital settings for both species and temperature:

Meters should be verified at least annually by comparing readings on known samples against oven-dry test results (AS/NZS 1080.1). Periodic calibration maintains confidence in field data and prevents drift between instruments.

In practice, resistance meters provide the most reliable in-depth measurement available on site. Use them as your “confirmation tool” after scanning with a capacitance meter, or as your primary device for delivery and pre-enclosure checks.

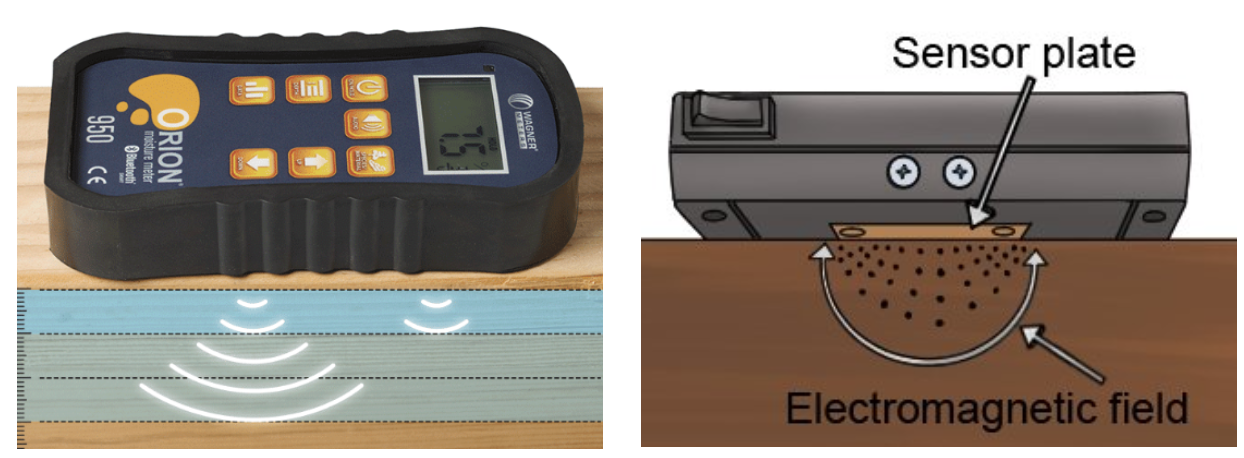

Capacitance meters, often called pinless meters, determine timber moisture content by measuring changes in its dielectric constant. The device emits a low-frequency electric field from a flat sensor plate placed against the timber surface. As the timber’s moisture content changes, so does its ability to store an electric charge. The meter converts this change into a percentage moisture value, typically calibrated against oven-dry reference data from AS/NZS 1080.1.

Figure 3: Use and mechanism of capacitance-type moisture meters

Capacitance meters are best viewed as the non-invasive scout in the moisture-measurement toolkit. They excel in identifying zones of elevated moisture during inspections of flooring, cladding, and mass-timber panels, especially where surface finish or appearance precludes pin testing. However, always follow up anomalies with resistance or oven-dry verification.

The oven-dry method determines the true moisture content of timber by measuring weight loss as all water is removed under controlled conditions.

A small sample is weighed, dried in an oven at a prescribed temperature until its mass remains constant, and then re-weighed. The difference between the initial and final mass represents the water content.

The oven-dry method is defined in AS/NZS 1080.1 Timber - Methods of test - Moisture content, which forms the benchmark calibration reference for all resistance and capacitance meters.

Figure 4: Oven baking of E. Nitens samples. Sirswal et al.

When in doubt, the oven-dry method provides the final word on moisture content. It should be used to resolve ambiguous or borderline site readings, or when establishing calibration baselines for new species, engineered timbers, or imported materials.

No single measurement method suits all situations. The choice depends on the purpose, level of accuracy required, and whether testing is being done on-site or in a laboratory.

Best practice is to use meters in combination. For example, capacitance meters can quickly locate high-moisture zones, which can then be tested with pin meters to confirm moisture depth and level. Where uncertainty remains, oven-dry testing should be undertaken.

Thermal imaging can be a valuable non-contact diagnostic method for locating areas of potential moisture accumulation before using moisture meters. Moist areas in timber components generally appear cooler than surrounding dry areas due to evaporative cooling and higher thermal conductivity.

Applications:

Practical guidance:

Even with the right tools, moisture measurement errors are common. The reliability of results depends on understanding the equipment’s limitations, applying proper corrections, and documenting readings in context.

Over time, moisture meters (especially capacitance models) can drift due to changes in internal circuitry, wear of sensor coatings, or environmental exposure. Even minor drift (1-2 % MC) can lead to non-compliance if left unchecked.

Always interpret readings relative to species, climate, and intended service condition. For example, a reading of 14 % MC might be ideal for interior framing in Adelaide but too high for a conditioned space in Sydney. Use local Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC) values as the benchmark, and verify results against NCC 2022 and AS 1684 requirements before proceeding.

Moisture readings have little meaning without context. Correct interpretation requires considering timber species, product type, and climate conditions at the time of measurement. Timber is continually seeking its equilibrium moisture content (EMC) with surrounding air, and readings should be assessed against what is normal for that environment.

Different species have unique cell structures and densities, which affect how moisture is stored and how meters respond.

For laminated or adhesive-bonded members, moisture distribution can be non-uniform:

Timber’s moisture content trends toward the Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC) dictated by local temperature and humidity. This relationship is illustrated below.

For example, flooring installed at 16% MC in Sydney may later dry back to 10-12% indoors, causing shrinkage if expansion joints are not detailed. Conversely, timber brought from a dry inland mill at 10% MC may swell when installed in coastal locations.

When evaluating site readings:

A reliable rule of thumb:

Timber should be installed within ±2 % of the expected EMC for its service environment.

Deviation beyond this range warrants investigation or acclimatisation prior to enclosure.

Accurate measurement of timber moisture content underpins every aspect of durability, serviceability, and code compliance. When readings are taken carefully, recorded systematically, and interpreted in context, they provide confidence that the structure will perform as designed for its full service life.

Moisture control is a construction and maintenance responsibility. Consistent, calibrated measurement protects projects from long-term decay, deformation, and costly remediation.