Publications

TBC

Moisture is one of the most influential factors affecting the performance of timber in buildings. Whether used externally or internally, timber will continually interact with ambient humidity and temperature, adjusting its own moisture content to reach balance with its surroundings. If this natural behaviour is not understood and properly accounted for during specification and installation, it can lead to problems such as warping, cupping, gaps, joint failure, or premature coating breakdown.

This page explores:

TBC

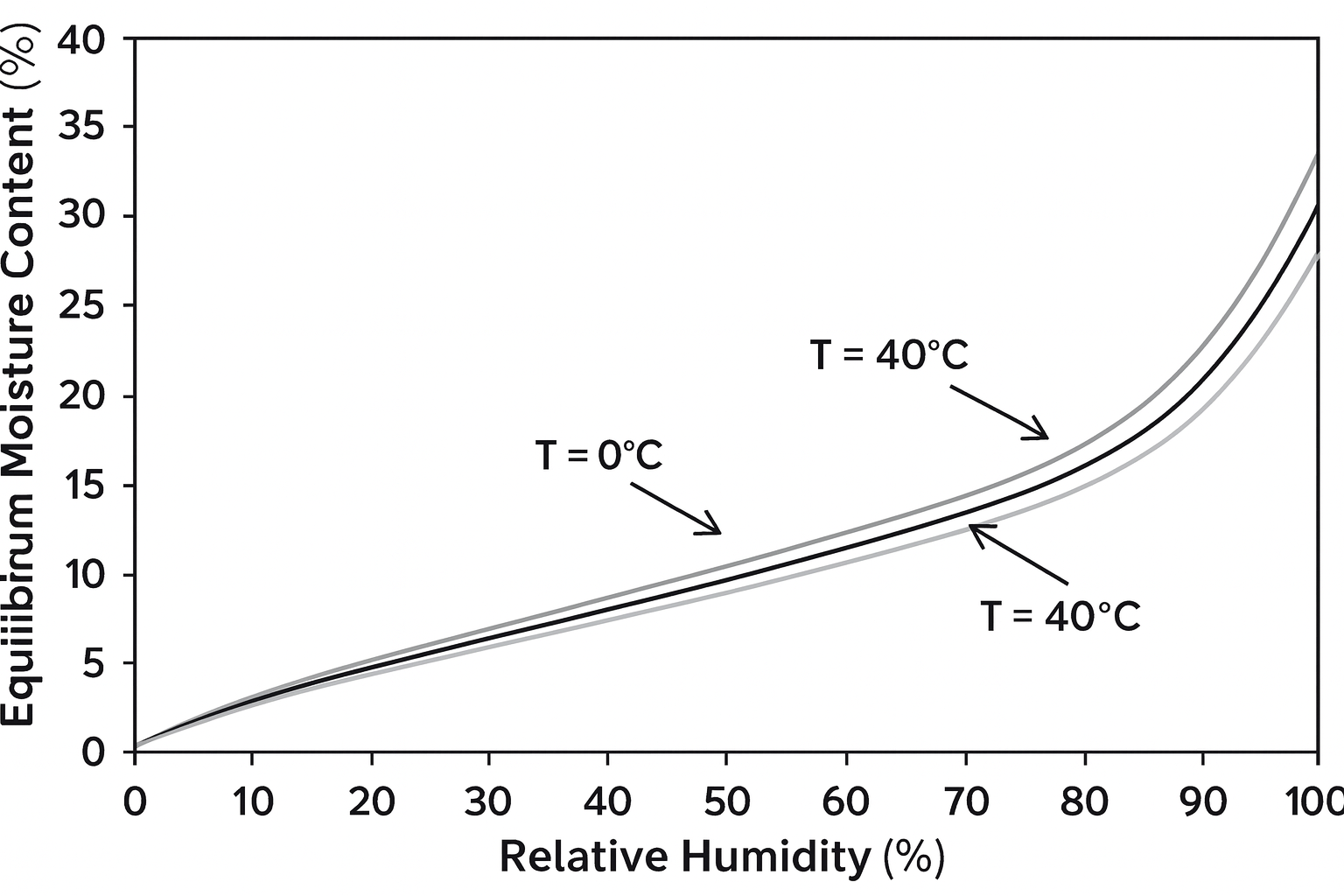

Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC) is the point at which timber’s moisture content stabilises in line with the surrounding environment. At EMC, the timber is neither absorbing nor releasing moisture. Because timber is hygroscopic, it constantly adjusts toward this balance in response to the local relative humidity and temperature.

Internal EMC generally ranges from 8-14%, depending on whether spaces are air conditioned or naturally ventilated.

External EMC is usually higher, around 12-18%, varying by climate zone and season.

Figure 1: Relationship between Relative Humidity and Equilibrium Moisture Content in timber at various temperatures

Key considerations

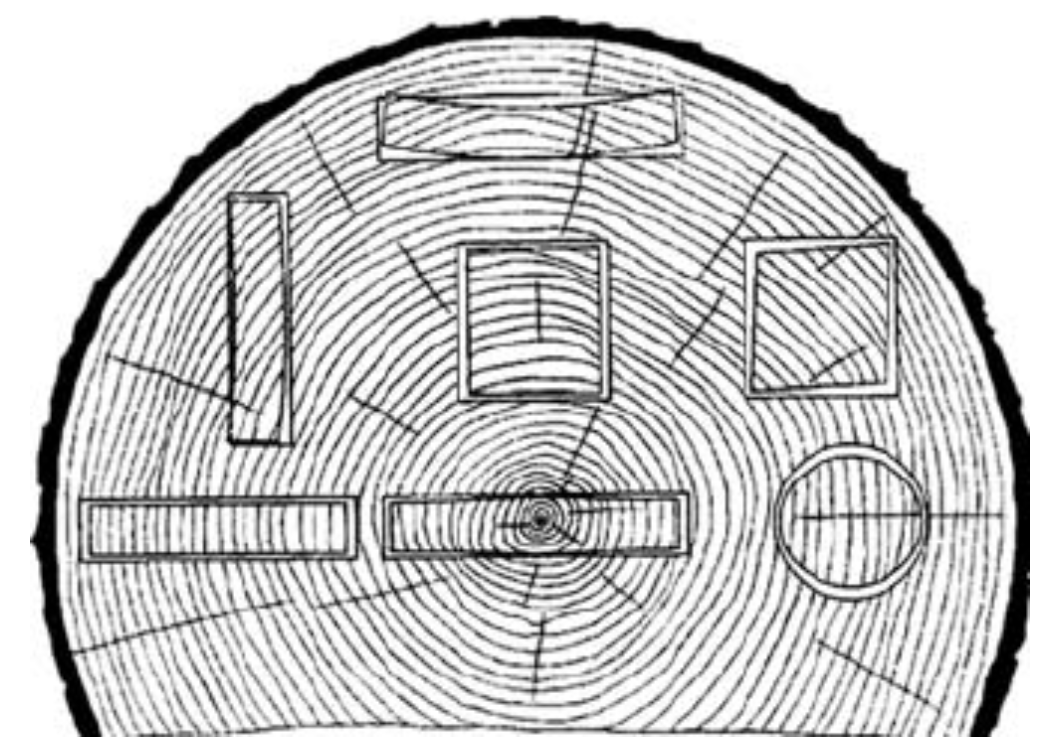

Timber is hygroscopic, meaning it naturally absorbs and releases moisture from the surrounding air. As it does so, it changes dimensionally-mainly across the grain-through shrinkage when it dries below fibre saturation point, and swelling when it absorbs moisture.

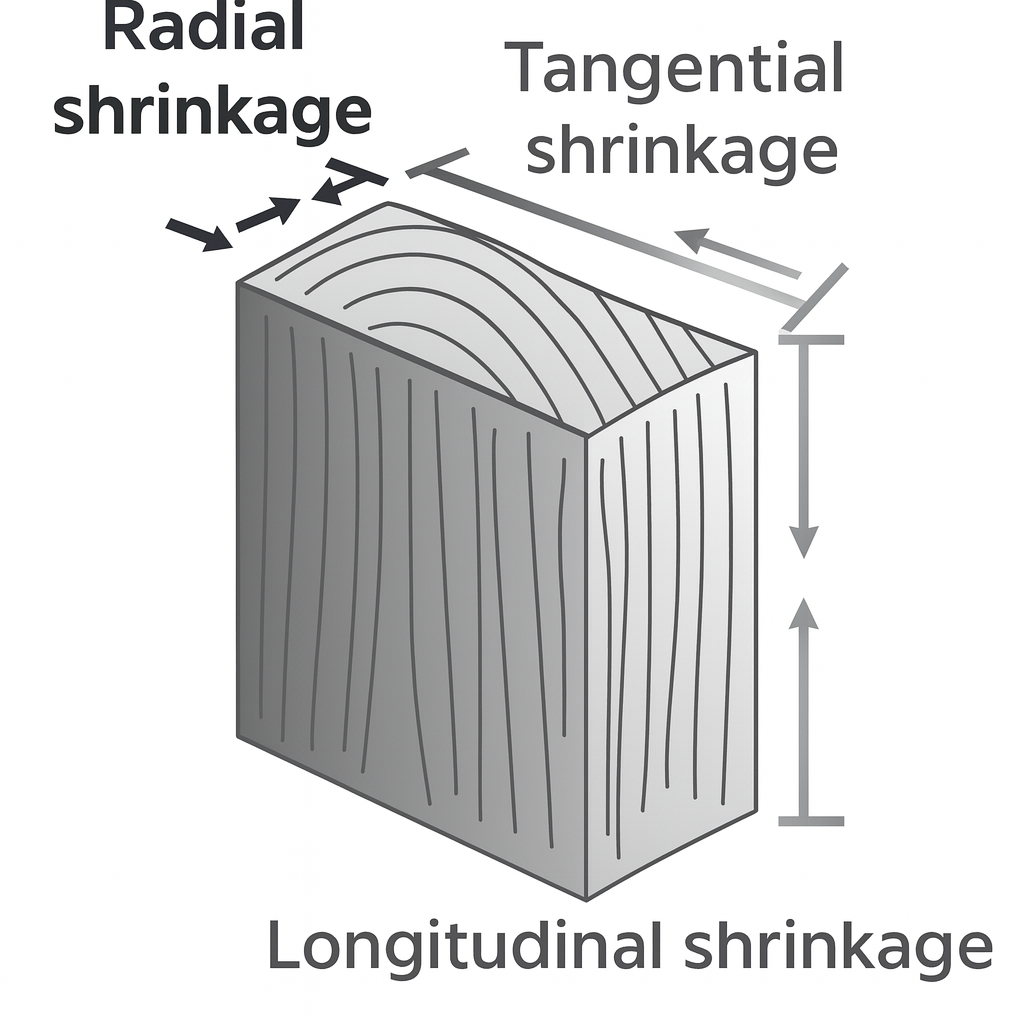

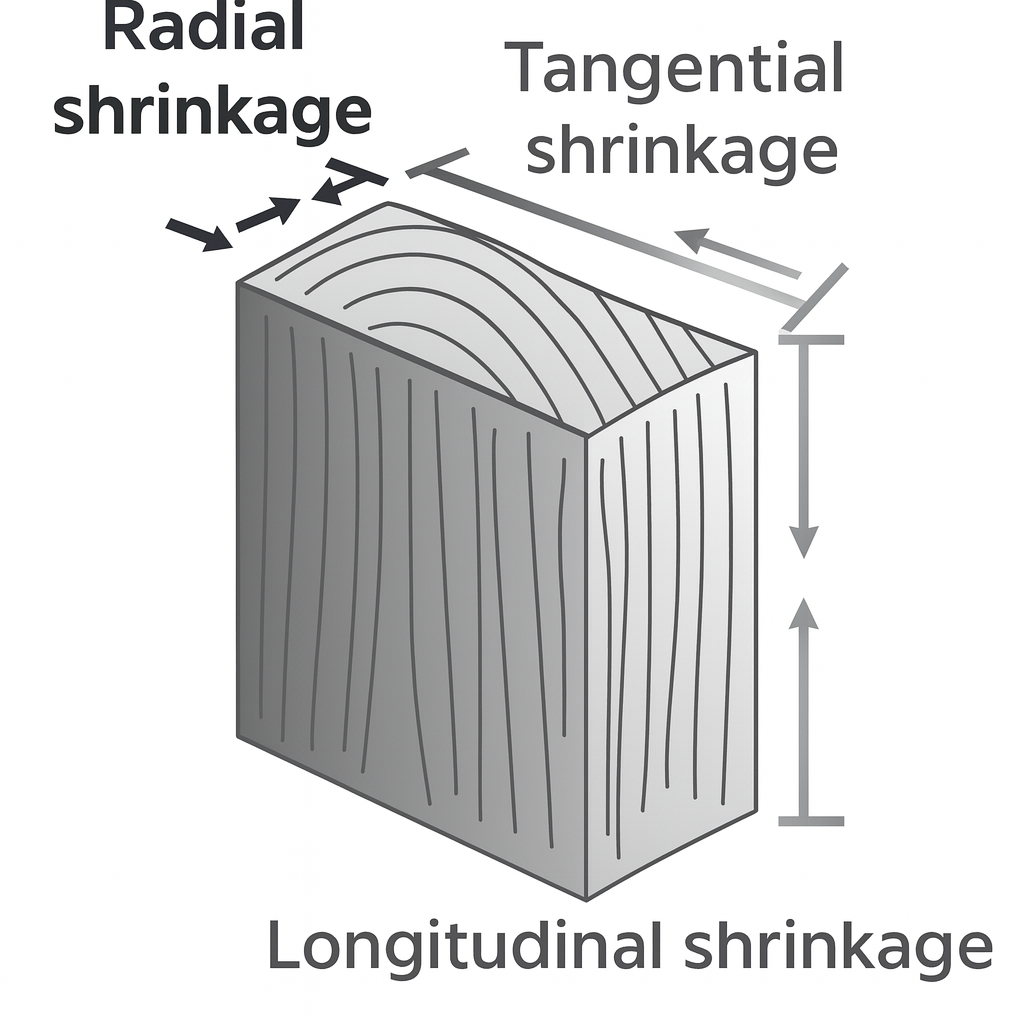

For most species, tangential shrinkage can be roughly 6-10% from green to oven-dry, while radial shrinkage is often half of tangential shrinkage.

Figure 2: Tangential and Radial Shrinkage.

If not accounted for, this natural movement can result in:

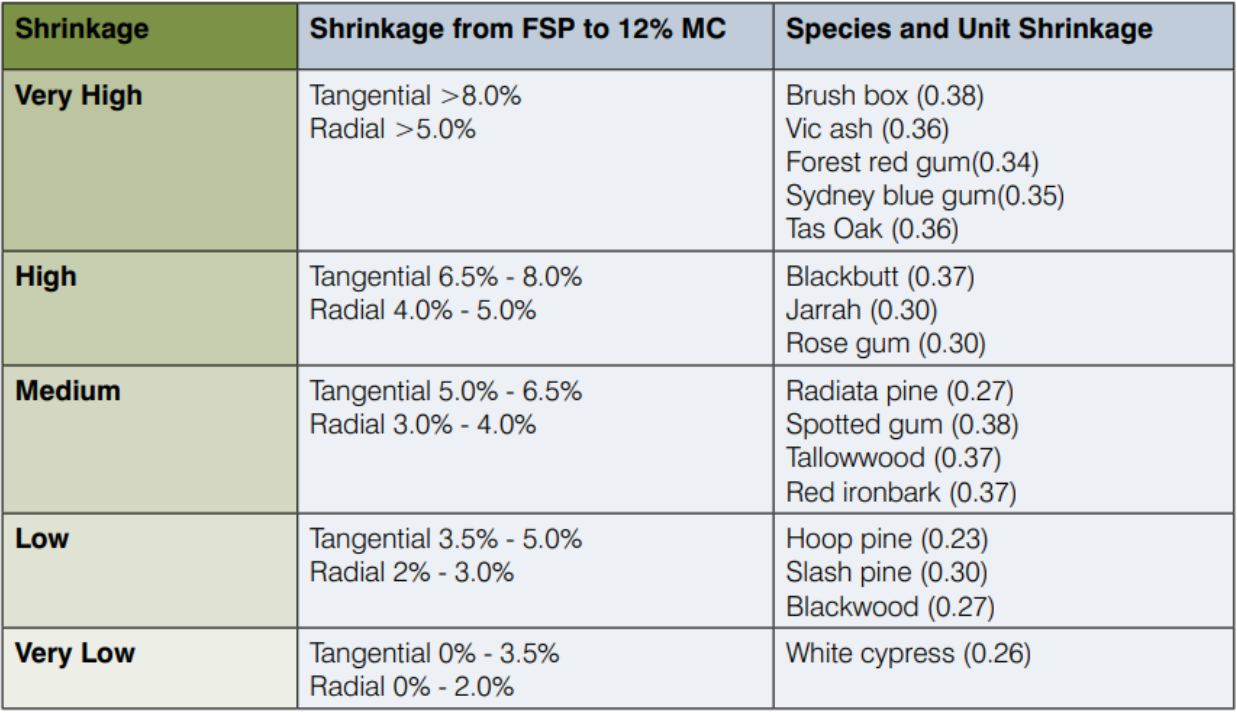

Species vary in shrinkage rates due to their cellular structure. Denser hardwoods often shrink more in absolute terms, but may still provide stable performance if properly dried and detailed.

Figure 3: Common Shrinkage Rates - TDG 14 p60

Moisture challenges don’t end with correct specification-site conditions often introduce unexpected risks. Timber may pick up additional moisture during transport or storage on site, or be exposed to rapid drying once installed in air-conditioned spaces.

Typical site risks

Good practice

Because timber will inevitably move with changes in moisture, good design and specification focus on managing this movement, rather than trying to eliminate it. By understanding timber’s response to moisture and specifying it to suit both the expected EMC and the site conditions, designers and builders can significantly reduce issues like shrinkage cracks, swelling jams, or coating failures. The key is to anticipate movement and design to accommodate it.

Figure 4: Left: Poor detailing, no gap - timber movement and failure. Right: Good detailing, sufficient space for timber movement.

Source: Timber With Ted Stubbersfield Newsletter July 2025

By selecting timber dried to a moisture content close to where it will stabilise in service, you reduce the extent of post-installation shrinkage or swelling.

By understanding how timber interacts with moisture - from the seasoning yard to the finished building - designers, specifiers and builders can make informed decisions that safeguard both appearance and performance. Ultimately, planning for movement and specifying to suit the timber’s final environment ensures the material’s natural advantages are fully realised, delivering projects that stand the test of time.