Publications

WS TDG 14 Timber in Internal Design

WS TDG 36 Engineered Woods & Fabrication Specification

WS TDG 13 Finishing Timber Externally

AS 1720.1, AS 2796, AS/NZS 1328.2

Selecting the right timber grades is critical to achieving both the structural and aesthetic goals of a project. Grades govern how timber performs under load, how it weathers over time, and how it looks in its finished state. This page helps designers, specifiers, and builders balance performance, appearance, and compliance, by explaining:

WS TDG 14 Timber in Internal Design

WS TDG 36 Engineered Woods & Fabrication Specification

WS TDG 13 Finishing Timber Externally

AS 1720.1, AS 2796, AS/NZS 1328.2

Structural grading ensures that timber products can safely carry design loads over the life of a building. It is the essential link between timber as a natural, variable material and its reliable use in engineered structures under the National Construction Code (NCC 2022).

In Australia, three principal grading systems are used, each tied to specific products and standards:

Understanding these systems, their reliability and variability, and where they are best applied is fundamental for design compliance and long-term structural performance.

F-grades apply to solid sawn timber graded by visual inspection, most commonly Australian hardwoods and some softwoods. Grading is performed by trained assessors under AS 2082 (hardwoods) and AS 2858 (softwoods), who look for characterisation like:

These features can indicate reductions in strength, so rules in the standards conservatively reject timber with defects beyond defined limits. This ensures that the remaining timber meets characteristic strength and stiffness values set by AS 1720.1. Typical grades include:

F5, F7: standard framing uses, light load members.

F14, F17, F27: heavier structural loads, such as large beams, bearers or portal columns.

Note on predictability:

Visual grading does not directly measure mechanical properties. While conservative, it leads to greater variability within a grade compared to machine-graded timber. This is acceptable and typical for many Australian hardwoods, which are not commonly machine graded.

MGP (Machine Graded Pine) is predominantly used for plantation softwoods like radiata pine. Unlike visual grading, machine stress grading directly tests the timber’s stiffness (modulus of elasticity) using bending machines, governed by AS/NZS 1748. This measured stiffness is statistically linked to bending strength.

MGP10, MGP12: common for studs, ceiling and floor joists.

MGP15: for longer spans or higher loads.

Machine stress grading provides more efficient use of timber resources and ensures tight performance reliability, because each piece’s properties are mechanically assessed by automated scanners which bend the timber slightly to measure stiffness. This ensures more consistent performance than purely visual grading.

Even machine-graded timber is subject to a supplementary visual check. This catches defects that might not significantly affect stiffness but could still undermine local strength - such as large knots or shakes. Typical applications:

Glue Laminated Timber (Glulam) is graded under AS/NZS 1328.1 and 1328.2, with grades from GL8 up to GL21, each reflecting a minimum bending strength and stiffness.

Because glulam is manufactured under strict controls, its strength and stiffness are very predictable, and large section sizes are possible without the inherent variability of sawn timber.

Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) is made by bonding thin veneers with the grain in a single direction, achieving high strength-to-weight ratios and consistent properties. It is rated by manufacturers typically as LVL13, LVL15 or similar, with certification under AS/NZS 4357. LVL is widely used for beams, floor joists and lintels, especially where long spans are required.

Practical note:

LVL is engineered to minimise natural defects (knots, slope of grain) and delivers reliable uniform strength. However, its appearance is generally more utilitarian unless specified with a decorative veneer.

Most buildings will incorporate several of these grading systems, tailored to the role each timber element plays:

Project documentation should always specify both species and grade, for example:

Spotted Gum F17, Radiata Pine MGP10, or GL13 Glulam to AS/NZS 1328.

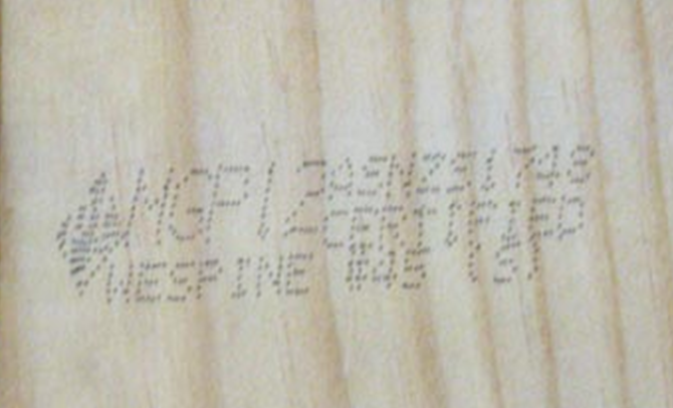

All structural timber in Australia must carry visible grading marks indicating compliance. Look for:

Figure 1: F grade stamp on LVL

Figure 2: Laser printed MGP grade label

Figure 3: GL grade label

While structural grading ensures timber meets engineering performance requirements, appearance grading governs how timber looks in finished applications. This is critical for exposed timber elements-such as internal linings, joinery, ceilings, feature posts or external cladding-where timber’s natural features are celebrated as part of the architectural aesthetic. Appearance grading manages the type, size and frequency of visible natural features, providing a benchmark for clients, designers and certifiers to agree on expectations.

In Australia, appearance grading for hardwoods is primarily governed by AS 2796.2, which defines allowable:

This standard underpins most local mill and supplier appearance grading practices. Common appearance grades include:

Figure 4: Select Grades to AS 2796 example. Source: TDG 14 p25

Timber is inherently variable. While structural grading governs strength and appearance grading manages obvious surface features, the deeper visual character of timber comes from its natural colour, texture and figure. These properties are inherent to each piece, shaped by species, growth environment, and even how the timber was cut and processed. They play a powerful role in the look and feel of finished spaces.Understanding these aspects helps designers and specifiers anticipate variation, coordinate finishes, and select the right timber for each visual intention.Even within a specified appearance grade, it’s normal to see:

These are not defects but part of timber’s organic characterisation. Selecting the right appearance grade ensures these features align with design intent.

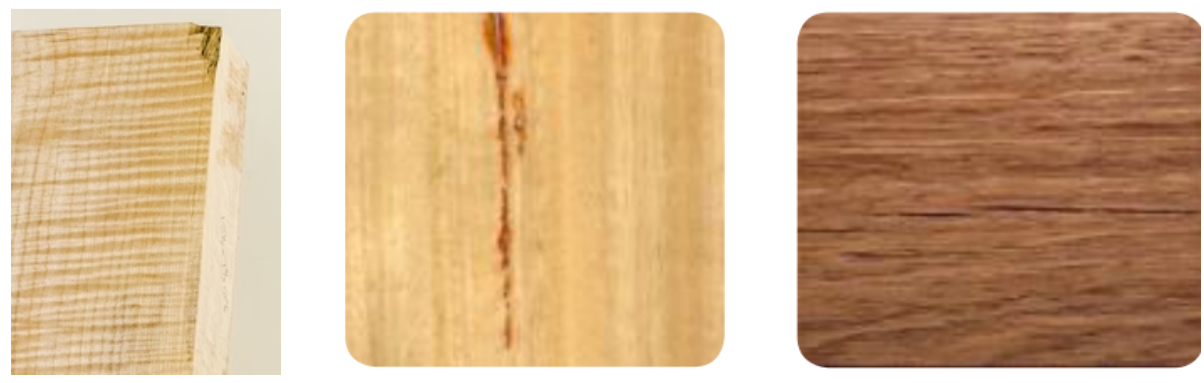

Figure 5: Common characterisation, fiddleback, gum vein, and surface check.

Timber colour comes from natural pigments and extractives in the wood. It varies:

Note: Colour is rarely a grading criterion under Australian Standards - it’s accepted as natural variation. Where a project demands tighter colour control, this needs explicit negotiation with suppliers (e.g. sorting to narrower colour bands).

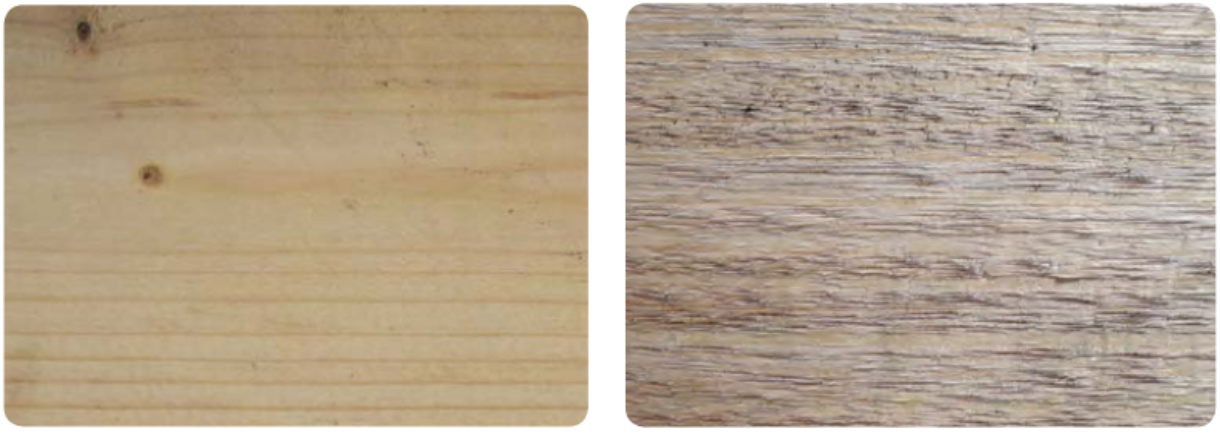

Texture refers to the relative size and density of the wood fibres:

Textureis influenced by:

This matters for finishing:

Figure 6: Texture examples, softwood sample exhibiting a fine texture, and a hardwood sample exhibiting a coarse texture.

Figure is the striking visual pattern caused by the wood’s internal structure beyond basic grain direction. It’s shaped by growth conditions, species quirks, and how the timber was cut. Examples include:

These natural effects are not defects - they are often the most valued aesthetic aspects, especially when enhanced by clear finishes or oils.

Figure 7: Curl, Birds Eye / Pommele, and Resin Pocket

When selecting timber for appearance, especially in exposed applications, consider:

Finish compatibility:

Tip: Always confirm expectations with clients using physical samples, not just species descriptions or grade labels. Each board is unique, and design stories are best told with realistic variation in mind.

Because timber is natural, boards will vary even within a grade. Best practice on site is to:

Selecting the right structural and appearance grades is not just a technical compliance exercise - it directly shapes the visual narrative and emotional feel of a space. The grade you specify effectively sets the rules for how much timber’s natural variability becomes part of the design story.

Well-chosen grades align the organic qualities of timber with architectural goals, whether that means highlighting flawless continuity or celebrating raw, rustic character.

For minimalist spaces where clean lines, subtle textures and uniform surfaces are priorities:

This combination supports contemporary interiors or commercial lobbies where natural material warmth is desired without overt natural irregularities.

If the architectural language celebrates timber’s natural story - knots, veins, subtle colour shifts - then Medium or High Feature grades are an intentional choice. They bring out:

This suits designs aiming for rustic, industrial, country or lodge-style expressions. It’s also a common choice for hospitality interiors like cafes and restaurants where character is more important than perfect uniformity.

It’s critical to differentiate between timber meant to be seen and timber concealed within walls or roofs:

This balance ensures you’re paying for visual quality only where it matters.

Your finish choice must always complement the grade:

Beyond style, think about how occupants will experience the timber up close:

Selecting the right timber is never just about ticking a box for compliance - it’s about ensuring every element of a building performs structurally and contributes to the intended design story. This guide has shown how:

Ultimately, matching grades and features to each design vision - from sleek minimalism to richly organic - ensures timber does more than just support a building; it becomes part of its character. Timber is unique among building materials for its combination of natural beauty, renewable credentials and structural versatility. By specifying grades thoughtfully, coordinating with finishes, and working closely with suppliers on expectations, you can deliver projects that meet both engineering and aesthetic ambitions - creating spaces that are strong, durable, and truly welcoming.